Aditya Ganapathiraju

ADA Knowledge Translation Center

Scores of Americans visit this country’s national parks and sites of interest every year. But for some, these visits can end up being an exercise in frustration as they try to navigate the accessibility barriers inherent in these historic sites. With this in mind, a community of forward-thinking citizens in St. Louis has been working together to make their landmarks more welcoming to everyone. They are doing this by incorporating principles of universal design into the city’s renovation plans.

CityArchRiver 2015 is a comprehensive renovation project that seeks to transform the Arch of St. Louis—the city’s iconic towering landmark—along with surrounding parks and museums into a more welcoming and accessible environment for visitors of all abilities. Because advocates of universal design were involved from the early stages of the process, the project has evolved into a remarkable example of how a space can meet the needs of everyone.

Universal Design

The Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University defines universal design as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without adaptation or specialized design.” Principles of universal design include concepts like “equitable use,” to accommodate for people with diverse abilities; “low physical effort,” so that a design can be used efficiently with minimum fatigue; and “size and space for approach and use,” to allow for use regardless of a person’s mobility or physical condition.

“When I had my chance,” Newburger said, “I emphasized accessibility and universal design. Eventually, the leader of the TAG—an architect—started raising universal design in every discussion.”

Newburger kept this momentum going by advocating for a group of citizens that would work to incorporate the needs of people with disabilities and offer their input and advice on the designers’ different ideas, especially whether they met the principles of a universally designed space. This became the CityArchRiver Universal Design Group, which was composed of people with disabilities who also had specific knowledge about how designs should be made universally accessible.

Members of the committee—most of whom were local disability advocates, healthcare providers, graduate students, lawyers, family members or other supporters—represented an incredibly diverse array of disabilities and needs, including people with quadriplegia and paraplegia, vision and hearing impairments, and psychiatric and developmental disabilities.

In addition to the Universal Design Group, Newburger and his colleagues emphasized the need to hire an architect with expertise in access and universal design. The leadership agreed and subcontracted Gina Hilberry of Cohen Hilberry Architects, who worked with Newburger on a variety of professional and volunteer consulting for the Mayor’s office. Hilberry’s expertise and ability to serve as a liaison between the committee members and the design teams was critical, and was just as essential to the undertaking as the Universal Design Group’s involvement.

Great Plains ADA Center Involvement

Chuck Graham, who served on the committee on behalf of the Great Plains ADA Center, said that the inclusion of the disability community during the beginning stages is what set the whole endeavor apart from the rest. Having served on dozens of committees over the past 30 years, Graham said that this early inclusion avoided the typical outcome of such projects, one where architects essentially finish the project and then seek input. This usually ends up in a suboptimal design for access or costly and time-consuming redesigning to remove barriers afterwards.

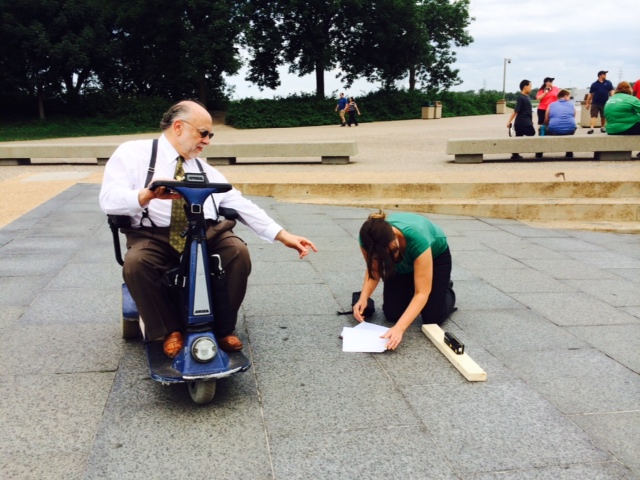

“It’s been no small undertaking,” Graham said, noting that this was a collaborative effort involving city, state, and federal entities that dealt with multiple buildings, parks, transit systems, business, and landmarks. The process was an ongoing monthly affair where the committee regularly interacted with the designers, often in ways that emphasized the very need for such a thorough process. For example, architects would bring scale models so the three blind members of the committee could more fully understand the proposals and changes being discussed.

Going Beyond ADA Compliance to Ensure Access

In practice, compliance with ADA standards—a legal requirement—does not guarantee that the space will be accessible for all.

The universal design group was not simply asking for more legal compliance, Newburger noted. Rather, the process of regular input, feedback, and negotiation is what ensured that the needs of everyone could be incorporated while avoiding the blind spots and oversights that can accompany large design projects. Power door operators, for example, are not required by ADA standards, yet this relatively inexpensive accommodation can mean the difference between folks who use walkers, crutches, and wheelchairs entering the building with ease or being left out in the cold.

Sometimes historic or natural landmarks are inherently inaccessible due to their fundamental design, as was the case with the top of the Gateway Arch. The top of the arch requires traversing a minimum of 96 steps, which implicitly restricts access by people with mobility impairments. Since the structure cannot be modified to be accessible, there are plans to create a video so that people who cannot visit in person can experience the view from the top.

Aside from those limited circumstances, great effort was taken to ensure access for all throughout the surrounding areas, which are fully accessible by ramps and elevators, as well as braille signage for those with vision impairments. Additionally, assistive listening devices and closed captioning is available for the theaters in the Arch complex and nearby Old Courthouse, with sign language interpretation available upon prior request. The National Park Service’s website even includes an insightful report about a visit to the Arch by a child with Asperger’s that helps visitors on the autism spectrum understand what to expect and how to prepare.

“This whole thing would not have happened had I not been able to obtain the support of the visionaries who are leading the project,” Newburger said, which came from “a combination of support from the Mayor’s office, relationship building, perseverance, making all communications diplomatic, and supporting of the visionaries’ personal goals.”

“I feel so proud of St. Louis,” said Colleen Burdiss, director of a local deaf services organization and member of the Universal Design Group, “and the fact that everyone was willing to work together so that everyone can enjoy everything that’s available.”

.png)