(Printer-friendly PDF version | 971 KB)

Knowledge Translation Center

Rapid Evidence Review

Technical Report

June, 2014

AUTHORS:

Sarah Parker Harris, Principal Investigator

Robert Gould, Project Coordinator

Kate Caldwell, Research Specialist

Glenn Fujiura, Co-Investigator

Robin Jones, Co-Investigator

Patrick Ojok, Research Assistant

Katherine Perez, Legal Research Assistant

Avery Olmstead, Academic Librarian

Table of Contents

Section 1: Background & Project Overview.

1.1. Aim of the Rapid Evidence Review.

1.2. Overview of Research to Date.

1.3. ADA Stakeholders & Knowledge Translation.

2.2.2. Categorical Coding & Supplementary Searching.

2.3. Creation of Research Questions.

2.5. Data Synthesis & Analysis.

3.1.2. Services/Service Providers.

3.1.3. Accommodation Requests.

3.2.2. Reasonable Accommodations.

3.2.3. Knowledge About the ADA.

Section 4: Discussion of Findings.

4.1. Knowledge About the Law..

4.2. Perception of Employability.

Section 5: Summary, Limitations & Next Steps.

5.3. Knowledge Gaps and Next Directions for Research

Appendix 1: Quality Appraisal Framework.

Appendix 2: Policy Domains (Categorical Coding)

Appendix 3: Thematic Codes that Cross-Cut Policies.

Appendix 4: Descriptive Codes (Keywording)

Appendix 5: Included Studies & Year of Publication.

Appendix 6: Interpretive Synthesis Arguments.

Evidence on the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) spans a wide range of resources and often is considered to yield conflicting results. On the cusp of the 25th anniversary of the ADA’s signing, there exists considerable need for consolidating this broad body of evidence to improve our understanding about the existing research and to assess the progress that has been made towards achieving the intended goals of the ADA. To address this need, the University of Illinois at Chicago is conducting a five-year multi-stage systematic review of the ADA as part of the NIDRR-funded National ADA Knowledge Translation Center, based at the University of Washington. The project comprises three stages: a scoping review, a rapid evidence review, and systematic reviews. This report provides a summary of the progress and findings from the second stage of the project – the rapid evidence review.

The purpose of the rapid evidence review was to undertake a preliminary assessment of the existing research and to pilot a review process that can be used for subsequent full systematic reviews. This report provides initial results about ADA evidence in relation to a research question that developed iteratively in response to the evidence and stakeholder feedback generated during the first year of this project (the scoping review): What evidence exists that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities? Moving forward, evidence from answering this review question and methodological insight gained from the process of conducting the rapid evidence review will be used to refine ADA research priorities and systematic review topics.

As the second stage of the systematic review project, the rapid evidence review process entailed:

- Eliciting stakeholder feedback on the results of the scoping review, both from the Expert Panel and the ADA National Network, to identify key research concerns and priorities.

- Using stakeholder feedback to refine inclusion criteria for conducting the rapid evidence review.

- Applying categorical codes to the scoping review research to identify and prioritize key policy domains (e.g. employment, health, assistive technology).

- Appraising the quality of evidence relevant to the selected policy domain for the rapid evidence review (employment) using an abbreviated assessment tool.

- Extracting and synthesizing evidence from the full text of ADA employment research and applying thematic codes.

- Analyzing the evidence using an abridged meta-synthesis approach.

- Generating and describing aggregate research conclusions about the ADA in relation to the research question.

Highlights of the Report

- 208 records relevant to employment were identified and reviewed.

- 118 records were generated from quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods analytical technique studies, and met the minimum standards of coding for inclusion in the rapid evidence review.

- 60 of the employment records contained evidence about the ADA’s influence on knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities.

- A novel review approach using adapted meta-ethnographic techniques was applied to develop the ADA-KT Synthesis Tool used for analyzing the existing research.

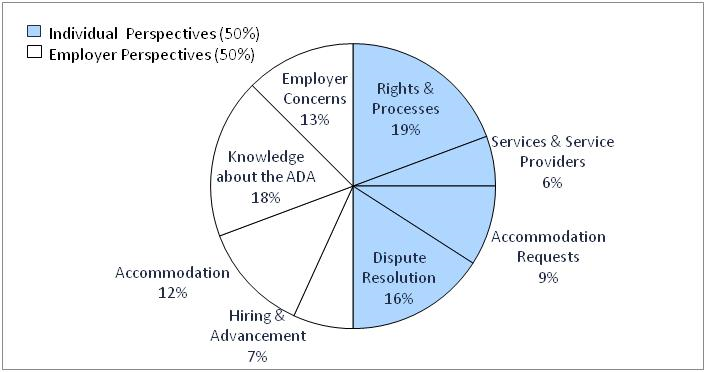

- Findings were synthesized into two main higher-order themes:

- Individual perspectives: related to knowledge about the ADA and experiences of employment.

- Employer perspectives: related to employing people with disabilities and employer responsibilities.

- Each main theme generated a number of synthesized subthemes (e.g. rights and processes; services and service providers; accommodation; dispute resolution; hiring and advancement; knowledge about the ADA; and employer concerns).

- The overarching findings that emerged from the synthesized research about the ADA’s influence in the area of employment in relation to knowledge, attitudes, and perception were centered around: knowledge of the law, the perceived employability of people with disabilities, and workplace culture.

1.1. Aim of the Rapid Evidence Review

The rapid evidence review spanned the second year of a five-year grant project funded by NIDRR to systematically review the broad range of social science research on the ADA. The grant is being funded as part of the NIDRR funded National ADA Knowledge Translation Center Project that was created in response to the call to increase the use of available ADA-related research findings to inform behavior, practices, or policies that improve equal access in society for individuals with disabilities. The UIC project addresses the call by undertaking a series of reviews of the current state of ADA-related research and translating findings into plain language summaries for policymakers, technical reports, publications in peer-review journals, and presentations at national conferences. The review process is being conducted across three different stages: (1) a scoping review of the full body of ADA research (completed 2012/2013); (2) a rapid evidence review that responds to key findings from the scoping review and provides a template for future review (completed 2013/2014); and (3) a series of systematic reviews to synthesize research and answer specific key questions in the identified research areas (to be conducted 2014-2016). The project will create a foundation of knowledge about the ADA, inform subsequent policy, research and information dissemination, and contribute to the overall capacity building efforts of ADA Regional Centers.

The current report contains the results of the rapid evidence review. Rapid evidence assessments examine what is known about a policy issue, and use systematic review methods to search and critically appraise the available research evidence in a strategic and timely way. These reviews limit particular aspects of the full systematic review process (i.e. by using broader search strategies, extracting only key variables, and performing a simplified quality appraisal) (Davis, 2003; Grant & Booth, 2009). They are undertaken with the view to be developed into full systematic reviews for use as protocols in future systematic reviews.

1.2. Overview of Research to Date

The systematic review project seeks to increase the utility of research on the ADA and thereby generate summative conclusions from the existing research evidence. The primary purpose of beginning with a scoping review in the first stage of the project was to provide a broad overview of current research on a topic, and to document key components of this research in order to identify specific gaps and key research needs based on existing evidence. The scoping review explored the following question: What English-language studies have been conducted and/or published from 1990 onwards that empirically study the Americans with Disabilities Act? The inclusion criteria for the evidence consisted of citations to all records identified as examining the ADA via a literature search using the following parameters: (a) published or dated from 1990; (b) written in English; (c) carried out in the United States; (d) relate to the ADA and (e) based on published studies reporting the gathering of primary or secondary data or the collating and synthesis of existing information to answer ADA-related research questions. Items that were not included were established facts about the ADA (i.e. court-case decisions, technical materials on compliance, general fact sheets), opinion pieces (i.e. by various stakeholders, lawyers, or academics), and anecdotal evidence.

The research questions, inclusion criteria, data screening, data selection, and data extraction procedures were developed by the research team in consultation with key ADA stakeholders. From the initial 34,995 records identified, 980 research records were included in the scoping review. The results were descriptively analyzed and synthesized into the following categories: record type, stakeholder groups, topics, and research methods. Approximately 51 per cent (499 records) of these were related to employment. Within the employment literature, the most prevalent types of records pertained to attitudes and knowledge, barriers and facilitators to implementation, assessments of compliance rate, and costs associated with the ADA. Further detail on the findings of the ADA scoping review can be found in the scoping review technical report (https://adata.org/scopingtechnical).

The results of the scoping review and feedback from key ADA stakeholders were then used to identify research priorities for the rapid evidence review (see the following section for further detail). Priorities included questions pertinent to employment, healthcare, education, compliance/accessibility, and assistive/information technology. These were determined to be critical areas of importance where rapid evidence and systematic reviews of the research will provide substantive evidence on the effects of the policy to illuminate its strengths, weaknesses, and research gaps. Of these areas, employment was deemed to be the most pressing priority.

1.3. ADA Stakeholders & Knowledge Translation

To ensure that the research generated through this project is relevant and topical, the research team continuously collaborates with key ADA stakeholders who have been instrumental in the drafting of policy, dissemination of research, and implementation of the ADA in practice. The research team works closely with an ADA Expert Panel, which consists of representatives from the National Council on Disability (NCD), the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF), the National ADA Network, Mathematica Policy Research Group, the US Business Leadership Network (USBLN), various Universities, and other pertinent organizations. In addition, the project team receives periodic feedback from the Directors (and other representatives) of the ADA National Network.

In February 2013, the UIC research team met with the Expert Panel and representatives from the ADA National Network to review scoping review findings and to identify or otherwise refine research topics and priorities. One priority topic identified was how the ADA impacts the full participation of people with disabilities – one of the primary goals stated in the preamble of the ADA. The key stakeholders emphasized that analysis of early research from national organizations, such as the National Council on Disability, is important to explore as a baseline point for tracking progress and development of research on the ADA. To inform the rapid evidence review, the stakeholders also identified the most pertinent review areas, based on their background and experience, as employment and healthcare.

The research team selected the topic area of employment for conducting the rapid evidence review due to its role as a key component in achieving full participation. More specifically, however, the ADA evidence on employment was also appropriate for the rapid evidence review because it provided a large amount of uncategorized research that would benefit from this type of analysis.

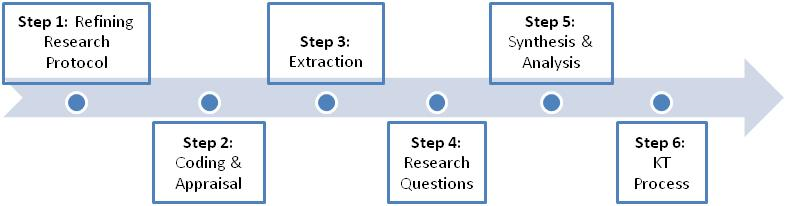

2.1. Methodological Overview

In an effort to address ADA stakeholder needs and in response to initial scoping review findings, the research team implemented a three-phase, six-step process for conducting a rapid evidence review that focused on the ADA employment research. The first three steps were part of the data collection phase, where the research team located and refined the evidence. Following initial data collection, the synthesis phase took place where research questions were iteratively created and answered (steps 4 and 5). The final phase of the process was Knowledge Translation (step 6), which comprised the dissemination of the current report and confirmation of the validity of the findings. Figure 1 below provides a visual representation of the rapid evidence review process:

Figure 1: Rapid Evidence Process

The first step of the rapid evidence review entailed refining the initial research protocol based on expert stakeholder input. To ensure that the evidence was specific to the topic of employment, the inclusion criteria from the scoping review was refined, a categorical coding scheme was applied, and additional searches were conducted. The evidence was then critically appraised using an abridged quality appraisal framework to ensure that the included records adhered to a minimum level of research reporting. In the third step, key findings and content descriptors were extracted from the full text records. The rapid evidence research question was then iteratively generated, and the evidence was synthesized and analyzed using a novel meta-synthesis technique (see subsequent sections for further detail on this step). The final step involved consultation with key ADA stakeholders to confirm findings and to identify priorities for the next stage of the systematic review project.

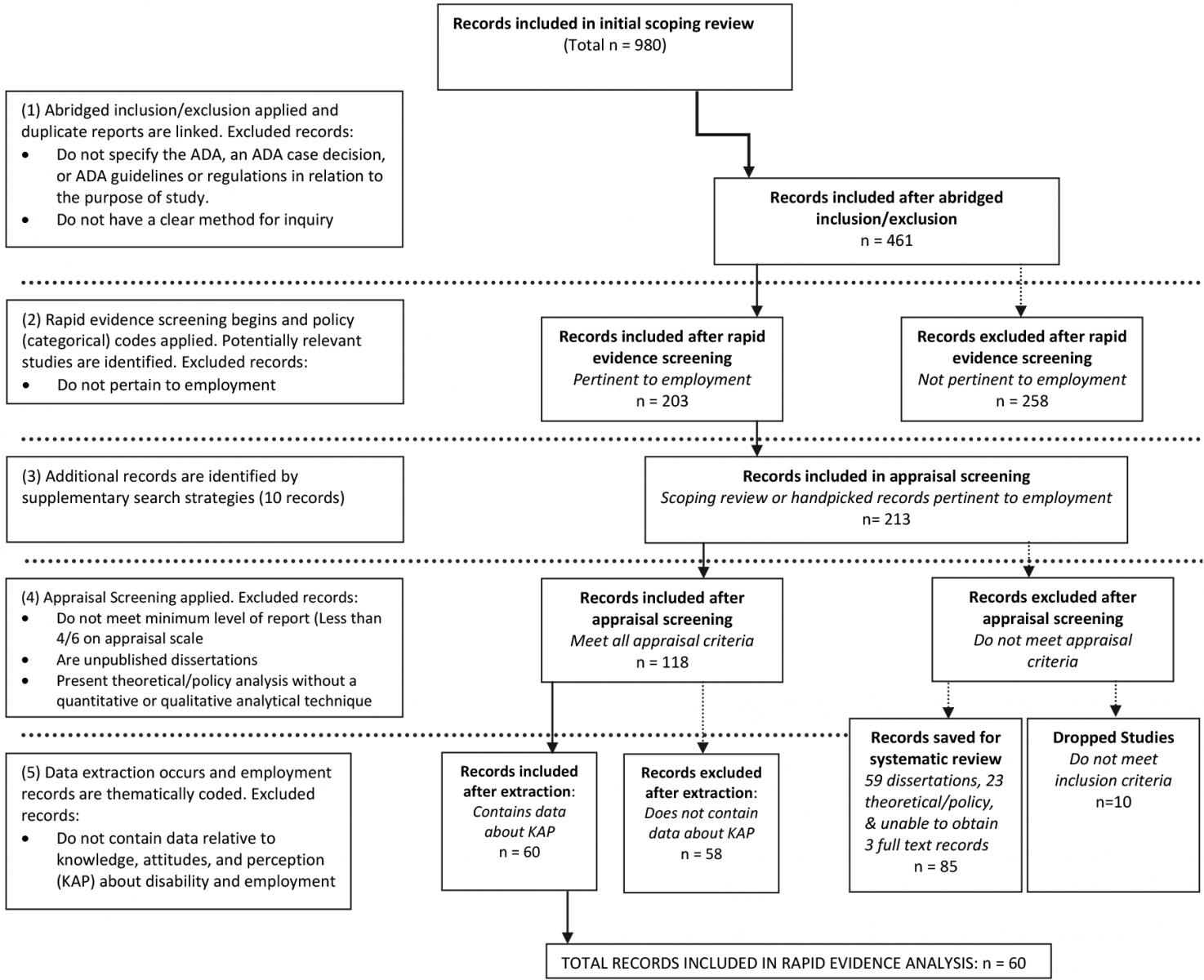

Figure 2: Scoping Review & Rapid Evidence Review Decision Tree

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection crosscuts three steps of the rapid evidence process: refining the protocol, coding and appraising the data; and extracting relevant records and evidence. Figure 2, presented previously, provides a visual representation of the data collection process. Following key stakeholder feedback to refine inclusion criteria for the rapid evidence review, 519 of the 980 records were excluded (461 included). Categorical coding was used to conclude that 203 of these records were pertinent to employment. The ADA Expert Panel and research librarian identified ten additional employment records. An abridged quality appraisal was applied to these 213 studies (203 from scoping review + 10 handpicked). 118 records adhered to the minimum level of reporting to be included in the rapid evidence review. Of these records, 60 were found to contain data relevant to address the research question under consideration. The process of identifying relevant records and refining the research question is explained in greater detail below.

Three changes related to the inclusion criteria were made to the protocol in response to stakeholder feedback about the scoping review. These changes helped to better distinguish between ADA research and ADA-related research so that only the most pertinent research was included. First, it was decided that only research records that specify the ADA, an ADA case decision, or ADA guidelines/regulations in relation to the purpose of study would be included. Second, a number of theoretical and policy records that were originally included in the scoping review were excluded as they did not meet the minimum level of academic rigor in reporting and making claims about ADA evidence. Finally, a number of included records that had presented duplicate findings of the same research – although published in separate years and with different titles – were excluded. The amended inclusion criteria were applied to the 980 scoping review records to reflect these changes. Subsequently, the revised rapid evidence inclusion criteria comprised records that:

- Were included in the scoping review.

- Specify the ADA, an ADA case decision, or one of the principal titles or guidelines within the law.

- Contain an explicit statement of the critical or theoretical framework and/or the method of analysis.

- Do not present duplicative reporting of a study that is already included in the review.

The revised criteria yielded a total of 451 potentially relevant records that were identified for inclusion in the rapid evidence review.

Following the initial appraisal screening using the refined protocol, categorical codes were applied to identify each policy domain stated within the purpose, goals, and/or research questions of the records. A list of categorical codes representing different ADA policy domains was deductively generated based on Expert Panel feedback. The categorical coding process was also used to further refine the evidence to ensure that records which addressed multiple policy domains were included. The categorical codes representing the disability policy domains include: employment, health, assistive/information technology, housing, education, transport, the criminal justice system, social welfare, emergency preparedness/response, recreation/public facilities, and civic engagement. During the second stage, 203 records relevant to employment were identified and met the inclusion criteria. The remaining 258 records were not pertinent to employment and were saved for future review.

Records that were initially excluded from the scoping review but that now met the refined rapid evidence inclusion criteria were also included. These records were located using an abbreviated search strategy – reviewing organizational reports/books previously excluded and conducting an updated search of NARIC’s (NIDRR’s online library resource) database for records published since the completion of the scoping review. Resulting from this process, 10 additional records pertinent to employment were identified and included in the rapid evidence review.

Following the location of employment-related records, a quality appraisal was conducted to assess that the records adhered to a minimum standard of research reporting (see Appendix 1). A full quality appraisal is customarily conducted in systematic reviews. However, for the purpose of a rapid evidence review, an abridged tool can be used to quickly and effectively assess quality of research. The abbreviated quality appraisal assessment tool used in this project was developed based on Dixon-Woods et al.’s (2006) tool for critical interpretive synthesis. The tool uses a binary coding (i.e. yes/no assessment) for key study design elements, and is applicable to both qualitative and quantitative research by including comparable questions for the different types of methodology. The mixed-synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research can be conducted simultaneously when appropriate indicators for appraising different methodological types are included in the framework.

One of the primary challenges of developing an appropriate appraisal tool for social policy research is in determining how to account for a variety of methodological approaches. For example, it can be particularly difficult to assess theoretical and policy review research where complications arise in separating opinion from fact. A common and longstanding critique when evaluating the impact of social policy or law is that scholarship often blends policy and opinion without empirical backing (see Kissam, 1988). In relation to ADA research, few studies outline a clear data collection strategy and empirical methodology for review. Moreover, many journals do not require an overview of methodology. Due to the ambiguity of assessing rigor in theory/policy records, the research team excluded this type of research from the rapid evidence assessment for future inclusion in the systematic reviews. Consequently, 85 records were excluded at this stage, which also included a number of organizational reports and dissertations (59 records) that were excluded due to the extensive time and resources it would take to review and categorize this large body of evidence.

The quality appraisal was conducted by two members of the research team who reviewed each record independently. The reviewers used the appraisal tool to locate a number of individual quality indicators. Only studies that adhered to a minimum standard of reporting (i.e. 4 out of 6 or 6 out of 6 quality indicators) were included in the rapid evidence review as high levels of evidence. To enhance the rigor of the appraisal process, the reviewers also coded relevant textual examples (using EPPI Review 4.0 systematic review software), to justify decisions about the minimum level of reporting and to assist in settling debates if there was disagreement about the appraisal process. A reliability score was also collected to assess consistency between reviewer scores. In the case of disagreements, differences between the two reviewers were reconciled by consensus until full agreement was reached on the quality of all items. Typically, 80 per cent or higher is considered standard for adequate coding. Initial agreement was reached on 115 out of 138 reviewable records (reliability score = 83%). The remaining records were assessed by a third reviewer, who confirmed the final appraisal score and decision to include or exclude.

Data extraction occurred in two stages, initial data extraction (called ‘keywording’) followed by a more detailed extraction of findings specific to the research question:

Initial Data Extraction: After obtaining the appraisal score, full-text records were reviewed and key information was extracted into a database file (using EPPI Review 4.0 systematic review software). Extracted information included descriptive data (e.g. bibliographic information) and content variables (e.g. study demographics, study design, research design). Outcome data (e.g. barriers and facilitators to implementation) are identified during the categorical coding process, where initial coding is used to generate a descriptive account of the records in preparation for a more detailed extraction of findings. During the keywording stage, the reviewers also applied thematic-codes to the records. These codes refer to the type of data reported in the evidence (i.e. direct reporting of data), the discussion (i.e. explaining what the data means), and the conclusions (i.e. suggestions for research based on collated evidence). A revised codebook for the rapid evidence review was developed deductively based on Expert Panel feedback and research team expertise. The thematic codes include: access, accessibility; attitudes, knowledge, perceptions; cost; compliance; information, communication; impact, outcomes; and program eligibility. Refer to Appendix 3 for descriptions of these codes.

Full Data Extraction: Once the research question had been iteratively generated, as outlined in the following section, a more detailed data extraction process occurred. The extraction of evidence (i.e. outcomes and findings) to address the key research question was conducted using an open-coding procedure where key concepts and findings were extracted from the data using data synthesis tools created in EPPI Review 4.0 to capture first-order (participant quotes/ direct data points) and second order (author analysis) constructs. Using framework analysis, reviewers applied a plain text code to summarize key points for the purpose of consolidating similar findings across research studies (see Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2011 for further explanation of this process). The key findings were extracted from the records using the “text in context” methodology suggested by Sandelowski, Barroso, and Voils (2007), where statements of findings reflect segments of data that are “understandable on their own apart from the data extraction sheets.” Direct quotes and coded data were used to inform the analysis and synthesis process, where the research team summarized key findings and synthesized key data for dissemination and use.

2.3. Creation of Research Questions

Following the thematic coding during the initial data extraction stage, a specific sub-topic was selected for the rapid evidence review using a three step process:

- Availability of Evidence: The topic was identified in area of research where there is a sufficient body of evidence that addresses a similar research problem. This is necessary to conduct a configurative assessment and evidence-based evaluation (Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2011).

- Knowledge of Evidence: The topic selection was informed by anecdotal claims about knowledge gaps within the wider body of evidence. The research team is closely oriented with the body of research so the reviewers are informed about repeated claims (Grant & Booth, 2009). In this project, the research team also drew on key reports from National Council on Disability that identified ADA research that has been substantially researched, but with minimal conclusions.

- Stakeholder Feedback: The research team consulted with the ADA Expert Panel and representatives from the ADA National Network to refine the research topic. Soliciting stakeholder feedback on topic selection during the development of research questions is a knowledge translation process that enhances the utility and relevance of systematic reviews (Graham et. al, 2006).

Following this process, the research team selected to focus on knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in relation to employment and the ADA for the rapid evidence review.

The two areas with the largest amount of evidence were records related to the employment rate of people with disabilities (36 records) and knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in relation to employment (60 records). Feedback from the ADA Expert Panel suggested that further review of employment rate research would be of little interest, and would likely result in highly contentious and incomplete findings. This is supported elsewhere in the literature. For example, Silverstein, Julnes, and Nolan (2005) argue that the impact of disability policy, such as the ADA, is not easily reduced to cause/effect relationships that can be tracked in large-scale census based data such as the employment participation rate. Additional feedback from the Expert Panel and the ADA National Network noted that knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in relation to employment was a key area of interest, relaying that conclusive summaries of the ADA evidence to date in this area would be highly beneficial to a wide variety of ADA stakeholders. The research team also had a familiarity with the common findings and gaps across this topic. Furthermore, national disability research had identified knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in disability employment as a priority area that requires both summative conclusion and new research directions (see for example, NCD, 2007; NOD, 2010).

This iterative process led to the development of the rapid evidence review research question: What evidence exists that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities?

2.4. Study Demographics

The database of records reporting on knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions within employment literature on the ADA included thirteen mixed methods, seven qualitative, and forty quantitative studies. The records reflect data collected between 1990 and 2007, and published between 1990 and 2013. There are nine records that have been published since 2007, but none report collecting data after 2007 (5 of the 9 records do not report when data was collected). The findings therefore exclude research on the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments of 2008. Additionally, two records include data collected before the ADA that were used to compare to data collected after the ADA went into effect (Gerber, Batalo & Achola, 2011; Hazer & Bedell, 2000). The publication dates and years of data collection for all included studies are reported in Appendix 5.

2.5. Data Synthesis & Analysis

Analysis was conducted using an adapted mixed methods meta-synthesis technique. Meta-synthesis has commonly been used as an umbrella term to refer to specific qualitative techniques, such as meta-narrative, meta-summary, and meta-ethnography (Jesson, Matheson & Lacey, 2011). These techniques share the goal of achieving a greater level of understanding of a field of knowledge, how it has been studied, and what empirical evidence there is across different research studies (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005). In all of these techniques, the term ‘meta’ is a reference to the end-goal of the research study. Meta-synthesis techniques do not seek to generate one generalized conclusion of something working or not working based on a shared finding across research studies, such as occurs through a meta-analysis. Rather, the ‘meta’ of meta-synthesis refers to the analysis, conclusions, and thick description of varied relationships within studies. The relationships are synthesized while maintaining and pinpointing the unique individual interpretations of high quality research evidence that is carefully chosen for analysis (Siau & Long, 2005).

The synthesis techniques for the rapid evidence review involved qualitative content analysis (generated from the data extraction) in addition to more advanced analysis techniques to explore the relationships and thematic components of the research literature. To enable mixed method data to be descriptively analyzed and synthesized, a qualitative content analysis approach is typically recommended (Arksey & O’Malley, 2010; Levac, Colquhoum & O’Brien, 2010). The constant-comparison method, using commonly listed checklist items, provides a useful starting point for developing an alternative iterative/comparative rather than aggregative model for synthesizing qualitative research (Barbour & Barbour, 2003). In the next stage of the project (full systematic review), synthesis of data will include comparative identification and analysis using adapted meta-ethnography techniques, where key concepts are compared, analyzed, and translated within and across studies. For the rapid evidence assessment, however, the research team analyzed and synthesized data by providing a descriptive numerical summary (e.g. overall number of studies included, types of study design, topics and/or titles studied, characteristics of disability sub-groups and/or stakeholders, years of publication); and thematic analysis using EPPI Reviewer 4.0 systematic review software.

The synthesis process is conducted to develop meaning from codes generated during the data extraction process. However, the diversity and quantity of evidence on the ADA presents more complicated challenges than in traditional rapid evidence assessments or systematic reviews. Conventional reviews have traditionally excluded qualitative research as the existing synthesis methods are better suited for quantitative research, such as with meta-analysis. Meta-ethnography offers an alternative approach for the synthesis of qualitative research, and there are a growing number of reviews that have employed meta-ethnographic synthesis. However, the field remains limited and existing examples are typically of small-scale reviews of qualitative studies (e.g. Britten et al. 2002; Cook, Meade, & Perry. 2001). Few studies exist that offer well-documented and tested tools for presenting, analyzing, and synthesizing mixed methods studies. The project team therefore created an ADA-KT Synthesis Tool (see Table 1), adapted from existing synthesis tools used by Britten et al. (2002) and Chang et al. (2010), in order to capture the diverse designs, methods, and content of ADA research.

Table 1: ADA-KT Synthesis Tool

|

Author & Year |

ADA Research Focus |

Study Goal |

Research Participants |

Design & Method |

Main Concepts/ Claims |

Interpretative Synthesis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from Britten et al. (2002) and Chang et al. (2010)

The ADA-KT Synthesis Tool captures methodological outcomes as well as the context of each study (i.e. author/date, research focus as it relates to the ADA specifically, the general study goal, participants, and design/method). The ‘main concepts/claims’ column refers to the explanations, quotes, data, and theories used by the authors of the original studies. The research team used their own words but preserved the meanings in the original studies as much as possible. The ‘interpretive synthesis’ column captures the research teams’ interpretations of the key concepts/themes in plain language text that is used to generate further analysis and comparison across research studies.

Using the ADA-KT Synthesis Tool, data was synthesized and analyzed for each record in relation to the research question. The research team individually appraised the full text article and identified key summative data. A database of each article and the relevant syntheses was created by the research team and forms the basis of analysis for the rapid evidence review. Findings from multiple studies were grouped together to make interpretative synthesis arguments, or analytical statements describing shared conclusions generated from the reviewed research. These conclusions are used to create synthesis arguments about what evidence exists in support of the key argument and/or findings. This analytical process (which is consistent with the type of analysis typically conducted during meta-syntheses), is intended to confirm knowledge about the current state of evidence and to create new knowledge by exploring the relationship of study findings between and across a diverse group of studies. Figure 3 charts the ADA synthesis arguments created across the studies.

Following the interpretive synthesis, the research team analyzed the data by analyzing relationships between the studies and generating higher-order themes (or categorical descriptions of shared synthesis arguments). The process of defining relationships between and across studies is a key component of analysis and is commonly referred to as ‘third order interpretation.’ To do this, the research team first noted trends, related findings, and discordant evidence across the research studies. Specific to the rapid evidence research question, this included findings directly relevant to knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions. Once the research team established the third order interpretation (i.e. by noting key arguments repeated across studies as indicated in Table 1), the next step was to develop higher-order themes (commonly referred to as ‘metaphors’). Table 2 below shows how the results from Table 1 are applied during the analytical process to create new thematic data.

Table 2: Higher Order Themes

|

Main Concepts/Themes |

Source(s) |

Explanation/Theory |

|

Higher order themes: the major ADA concept/theme that range across studies |

The different studies in which the concepts/themes are embedded. |

Authors’ and reviewers’ synthesis of the concepts/themes |

Source: Adapted from Paterson, Thorne and Dewis (1998) and Chang et al. (2010)

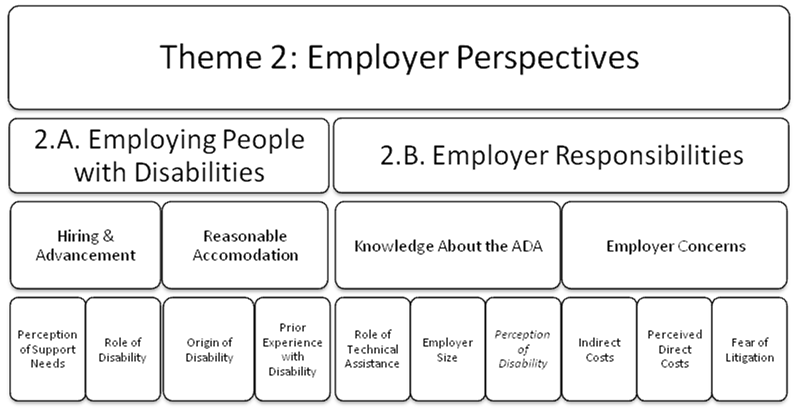

The identification of higher order themes is a collaborative process, where members of the research team combine individual assessments of the synthesized data to generate a configurative analysis. Gough, Oliver, and Thomas’ (2011) description of open-thematic coding for systematic review informed this process. Two higher-order themes of synthesis arguments were identified that suggest the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities: (1) Individual Perspectives and (2) Employer Perspectives. A number of subthemes of related syntheses also emerged within each of these higher order themes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Higher Order Themes & Subthemes of Related Synthesis Arguments

The primary purpose of identifying the broad thematic categories is to present research syntheses in a way that portrays how individual results are related to each other. These themes are not mutually exclusive, as the records may contribute to synthesis arguments found in multiple subthemes. The process of identifying subthemes allows for the grouping of similar findings across study contexts for analytical purposes. The following section describes the findings and is organized around the two new higher order themes and subthemes.

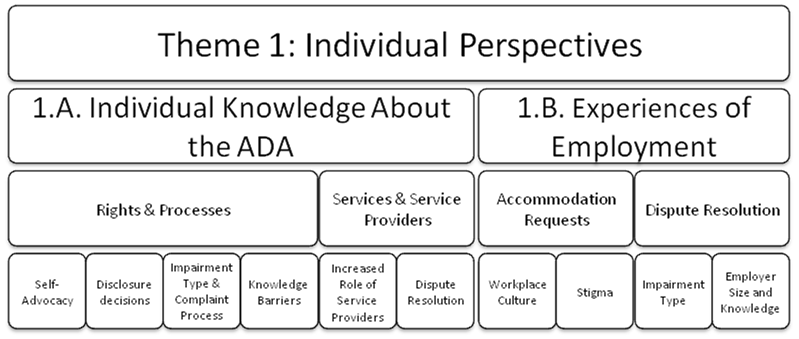

3.1. Individual Perspectives

The first thematic category of evidence relates to individual perspectives. Evidence exists that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities from the individual perspective across four synthesized subthemes of findings. The first two subthemes (rights/processes and services/service providers) pertain to individual knowledge about the ADA. The second two subthemes (accommodation requests and dispute resolutions) relate to individual perspectives about employment experiences. Table 3 provides a visual relationship of the themes, subthemes, and synthesis arguments pertaining to the ADA and individual perspectives about the employment of people with disabilities.

Table 3: Hierarchy of Individual Perspectives

Higher Order Themes, Subthemes & Synthesis Arguments

The subtheme of rights and processes refers to an individual’s knowledge about their rights under the ADA and how to apply the ADA. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Self-Advocacy: People with disabilities’ self-advocacy skills have developed in relation to knowledge about their rights under the ADA. There is evidence that individual knowledge has grown in relation to increased choice and access. There is also evidence that the growth of self-advocacy skills has come out of necessity due to limited knowledge of the ADA by employers (Blanck, 1996; Gerber, Batalo, & Acaolo, 2011; Thompson & Dickey, 1994).

Disclosure Decisions: There is evidence to suggest a relationship between ADA knowledge and disclosure, but it is not possible to report conclusively on this relationship in the rapid evidence review. Further discussion about this gap in the research is included in section 5.3.

Impairment Type & Complaint Process: People with cognitive impairments experience barriers while filing formal ADA complaints to the EEOC due to lack of knowledge about the complaint process. This evidence is derived from the notion that people with cognitive impairments are most likely (compared to other types of disability) to have formal ADA complaints dismissed due to improper filing before they have a chance to be reviewed in full (Unger, Campbell, & McMahon, 2005; Van Wieren, Armstrong, & McMahon, 2012).

Knowledge Barriers: People with stigmatized disabilities and/or more complex accommodation requirements have increased knowledge barriers to applying their rights under the ADA during the job search process. This evidence comes from people with disabilities expressing difficulties or insufficient knowledge about how to apply the ADA to their individual job searches (Gioia & Brekker, 2003; Goldberg, Killeen, & O’Day 2005; O'Day, 1998; Price, Gerber & Mulligan, 2003; Thompson & Dickey, 1994).

This subtheme is regarding the role of the ADA on services and service providers, primarily as it relates to rehabilitation counselors. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Increased Role of Service Providers: Rehabilitation counselors and other professionals can and should have an increased role in providing information/knowledge to people with disabilities on how to apply and use the ADA. The evidence is primarily derived from research in rehabilitation counseling that interrogates the changing roles of service providers since the ADA (Gordon, Feldman, Shipley & Weiss, 1997; Neath, Roessler, McMahon & Rumrill, 2007; Rumrill , 1999; Rumrill, Roessler, Battersby-Longden & Schuyler, 1998).

Dispute Resolution: When rehabilitation counselors inform people with disabilities about ADA processes prior to job placement they are more likely to prevent disputes that end in discharge. Evidence demonstrates that when training or information is provided early in employment processes, formal disputes are often avoided (Neath, Roessler, McMahon & Rumrill, 2007; Rumrill , 1999; Rumrill, Roessler, Battersby-Longden & Schuyler, 1998).

This subtheme is in regards to the ADA’s influence on accommodations requests. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Workplace Culture: Workplace culture impacts decisions to disclose and to request accommodation. The evidence is underpinned by the notion that anticipated disruption to routine workplaces continues to influence accommodation requests by individuals. There is evidence to suggest that this weighs into decisions by both employers and people requesting accommodations, although there is less knowledge about how often this plays into individual’s decisions to request (Baldridge & Veiga, 2001 & 2006; Gioia & Brekker, 2003; Madaus 2006 & 2008; Matt, 2008; Nachreiner, Dagher, McGovern, Baker, Alexander & Gerberich, 2007).

Stigma: Perceived stigma influences the decision to disclose disability for accommodation requests. There is evidence that fear of both explicit and implicit discriminatory attitudes prevent decisions to request accommodations (Gioia & Brekker, 2003; Goldberg, Killeen, & O'Day, 2005; Price, Gerber & Mulligan, 2003).

The final subtheme is in regards to formal and informal dispute resolution processes. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Impairment Type: Outcomes of formal dispute resolution are affected by different types of impairment. Evidence for this finding is derived from secondary analyses of data generated from the EEOC IMS. While secondary data does not provide direct evidence about knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in relation to the employment of people with disabilities, it does provide suggestions about potential relationships between individual knowledge and characteristics of plaintiffs (for example descriptions about the industry types of businesses involved in the ADA disputes) (Conyers, Boomer, & McMahon, 2005; Lewis, McMahon, West, Armstrong, & Belongia, 2005; McMahon, Shaw, West & Waid-Ebbs, 2005; Moss, Swanson, Ullman & Burris, 2002; Neath, Roessler, McMahon & Rumrill, 2007; Snyder, Carmichael, Blackwell, Cleveland, & Thornton III, 2010; Tartaglia, McMahon, West, & Belongiac, 2005; Unger, Campbell, & McMahon, 2005; Unger, Rumrill & Hennessey, 2005; Van Wieren, Armstrong, & McMahon , 2012).

Employer Size & Knowledge: The number of disputes filed is jointly influenced by employer size and individual knowledge of the formal complaint process. There is evidence to suggest that the size of the business and the knowledge of its employees are interrelated factors that impact the frequency of disputes (McMahon, Rumrill, Roessler, Hurley, West, Chan, & Carlson, 2008; Tartaglia, McMahon, West, & Belongiac, 2005; Van Wieren, Armstrong, & McMahon, 2012). There is insufficient evidence at this time to comment on the magnitude of the relationship or to conclusively identify underlying factors contributing to the relationship.

3.2. Employer Perspectives

The second thematic category of evidence relates to employer perspectives. Evidence exists that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities from an employer’s perspective across four synthesized subthemes of findings. The first two subthemes (hiring/advancement and accommodation) relate to employers perspectives about employing people with disabilities. The second two subthemes (knowledge about the ADA and employer concerns) relate to employer’s responsibilities under the ADA. Table 4 provides a visual relationship of the themes, subthemes, and synthesis arguments pertaining to the ADA and employer perspectives about the employment of people with disabilities.

Table 4: Hierarchy of Employer Perspectives

Higher Order Themes, Subthemes, & Synthesis Arguments

This subtheme manifested in regards to perceptions of disability in hiring or advancement decisions. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Perception of Support Needs: Hiring and advancement decisions are impacted by anticipated need for accommodation and on the job supports. The evidence demonstrates that employers take into account the potential complexity of an accommodation when making hiring decisions (Dowler & Walls; 1996, Hazer, & Bedell, 2000).

Role of Disability: Employers report concerns about the abilities of people with disabilities while concurrently reporting that disability does not factor into hiring and advancement decisions. The evidence indicating that disability does not factor into employment decisions is explained as a potential indication of public perception bias, meaning that individuals may report what they anticipate should be the appropriate answer as respondents are unlikely to report non-compliance (Bruyère, 1999; Houtenville & Kalargyrou 2012; Kaye, Jans & Jones, 2011; McMahon, Shaw, West & Waid-Ebbs, 2005).

The subtheme is in regards to the provision of reasonable accommodations. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Prior Experience with Disability: Willingness to provide accommodation is influenced by previous experience with disability. The evidence shows that the more exposure that employers have, or have had in the past, to working with people with disabilities, the greater the willingness is to provide reasonable accommodations (Hernandez et al. 2004; MacDonald-Wilson, Rogers, & Massaro, 2003; Popovich, Scherbaum, Sherbaum, & Polinko, 2003).

Origin of Disability: There is evidence to suggest a relationship between decisions to disclose and perceptions about origin of disability, but it is not possible to report conclusively on this relationship in the rapid evidence review. Further discussion about this gap in the research is included in section 5.3.

Both these findings confirm that the ADA has not been able to positively influence knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities. This evidence exemplifies how extralegal factors continue to impact decisions regarding implementation and compliance for some businesses.

Employer knowledge of the ADA was found to be a subtheme. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

The Role of Technical Assistance: Lack of knowledge about the availability of technical assistance affects responsiveness to and compliance of reasonable accommodations. The evidence demonstrates how companies that have difficulties in providing accommodations often have limited knowledge of outside resources for assistance (Bruyère 1999; Slack, 1996; Unger & Kregel, 2003; Wooten & Hayes, 2005).

Employer Size: The size of the employer impacts knowledge of and compliance with the ADA. There is no consensus in the research as to the direct relationship between company size and knowledge. Rather, the evidence shows that there is a relationship between business size and the way knowledge/compliance is achieved (Waters & Johanson, 2001; Conyers, Boomer, & McMahon, 2005; Lewis, McMahon, West, Armstrong, & Belongia, 2005; McMahon, Rumrill, Roessler, Hurley, West, Chan, & Carlson, 2008; McMahon, Rumrill, Roessler, Hurley, West, Chan, & Carlson, 2008; Popovich, Scherbaum, Sherbaum, & Polinko, 2003).

Perception of Disability: Knowledge of the ADA does not translate into changing attitudes about hiring people with disabilities. The evidence shows that there is no direct relationship between knowledge of the ADA and hiring decisions, nor is there any evidence that the way an employer gains knowledge about the ADA changes attitudes towards people with disabilities. There is only a minimal amount of evidence showing that there are overtly negative perceptions about people with disabilities in relation to the ADA (Hazer, & Bedell, 2000; McMahon, Rumrill Roessler, Hurley, West, Chan, & Carlson, 2008; Robert & Harlan, 2006 ; Scheid 1998; Slack, 1996; Thakker & Solomon, 1999).

The final subtheme is regarding employer concerns of applying the ADA in the workplace. In this area, the synthesized findings of the research evidence show that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities in relation to:

Indirect Costs: employers are concerned about decisions to hire and/or provide accommodations in relation to anticipated disruptions to workplace culture. The evidence shows that people in charge of hiring and accommodating workers weigh decisions about compliance against the potential for disrupting existing workplace practices (Florey & Harrison, 2000; Roessler & Sumner, 1997).

Perceived Direct Costs: Employers are concerned about disability and/or people with disabilities in relation to the perceived costs of job restructuring and modification, accommodations, and workers compensation claims. This body of research is used to explain employers’ hesitancy in employing people with disabilities (Florey & Harrison, 2000; Roessler & Sumner, 1997; Gilbride, Stensrud & Connolly, 1992; Hernandez, Keys, & Balcazar, 2000; Houtenville & Kalargyrou, 2012; Kaye, Jans & Jones, 2011; Roessler & Sumner, 1997, Soffer & Rimmerman, 2012).

Fear of Litigation: Employers are concerned about hiring people with disabilities due to the fear of potential litigation and the perceived cost of that litigation. In early ADA research, there were anecdotal claims about how employers’ fear of litigation impacted the labor market participation of people with disabilities. (Kaye, Jans & Jones, 2011; Moore, Moore, & Moore 2007; Satcher & Hendren, 1992; Schartz, Hendricks, & Blanck, 2006).

The above findings jointly demonstrate that employers’ initial fears of the ADA relate to concerns about job restructuring, modifying workplace culture and processes, and accommodations. Moreover, that this has changed very little in the past 25 years.

The consolidated body of research evidence on ADA supports three key claims. These claims reflect how the findings configuratively relate to each other and to the broader research question. Configurative analysis in systematic reviews is used to translate the meaning of findings between and across studies (Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2012). From this process, there is substantial evidence to suggest that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in the area of employment with regards to: (1) knowledge of the law; (2) perception of employability; and (3) workplace culture. These are discussed below.

4.1. Knowledge About the Law

The ADA research evidence shows that there are some employers who maintain baseline knowledge of compliance while leveraging this knowledge to avoid the ‘spirit of the law.’ While it is not possible to conclude how widespread this phenomena is, there is evidence covering a range of time across different studies that suggests this is an ongoing concern about ADA implementation. The need to address this concern becomes apparent when coupled with the existing evidence about people with disabilities and their knowledge of the ADA. People with disabilities concurrently experience barriers to knowledge that affect development of their rights and processes under the ADA. For example, employers have widespread concern about skill levels of people with disabilities while also reporting that disability does not factor into their hiring and advancement decisions. For people with disabilities, increased knowledge of the ADA provides individuals with a resource for self-advocacy with enhanced legal protections. Together, this evidence suggests the need for a different type of knowledge translation that more fits the spirit of the ADA.

4.2. Perception of Employability

The ADA research evidence shows that stigmatized perceptions of disability impact a variety of employment decisions, including hiring, advancement, and providing reasonable accommodation. For example, individual determinations about type of disability and if the disability is considered ‘deserving’ of accommodation can influence determinations of the ‘reasonableness’ or perceived ‘fairness’ of accommodations. Correspondingly, people with disabilities who perceive stigma are less likely to disclose for the purpose of requesting accommodations. Together, this evidence suggests that although the ADA has made acting upon the basis of overtly prejudicial attitudes illegal, more implicit forms of discrimination continue to influence perceptions of employability.

4.3. Workplace Culture

The ADA research evidence shows that fear of disrupting workplace culture prevents people with disabilities from exercising their rights and responsibilities under the ADA. For example, disclosure and requests for accommodation may affect workplace practices. There is evidence that employers factor anticipated changes to existing policies and practices into their decisions of reasonableness. Correspondingly, evidence exists that fear of disrupting workplace culture also impacts employer decisions about the perceived reasonableness of accommodations and making hiring decisions. There is also evidence that some people with disabilities anticipate this calculation, and may choose not to request accommodation. Together, this evidence suggests that flexibility in the workplace can be conducive to both individual requests and employer responsiveness.

5.1. Summary

A rapid evidence review process was used to undertake a preliminary assessment and synthesis of the ADA employment research, focusing on the following research question: What evidence exists that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the employment of people with disabilities? Drawing on the findings from the scoping review of the ADA research conducted in year one of the project, the research team identified 208 records relevant to employment. Using an abbreviated quality appraisal tool, 118 records met the minimum standards of coding for inclusion in the rapid evidence review. From these, 60 records contained evidence specific to the research question. These records were synthesized and analyzed using an adapted meta-synthesis approach. The research evidence shows that the ADA has influenced the following areas: individual knowledge and experiences of employment (e.g self-advocacy, impairment type/stigma, role of service providers, dispute resolution/complaints, workplace culture); and employer perspectives and responsibilities (e.g. accommodations, role of disability, technical assistance, indirect/direct costs). The consolidated body of research evidence on the ADA supports three key claims: that the ADA has influenced knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in the area of employment with regards to: (1) knowledge of the law; (2) perception of employability; and (3) workplace culture.

5.2. Limitations

The primary limitation involved the abridged search strategies used to identify relevant research. A number of records (i.e. dissertations, theoretical articles and organizational reports) were excluded due to time and resource constraints associated with conducting a rapid review. The search process for rapid evidence reviews is intentionally abbreviated to establish a rigorous process that can be expanded upon for future systematic review. It is not meant to detail an exhaustive body of literature on the subject. Supplementary topic-specific searches will be conducted in the full systematic reviews to provide a more complete overview of available research, which will span a smaller group of studies.

A second key limitation of the rapid evidence review involved the need to continually refine the methodological process, especially in the stages of synthesis/analysis. This resulted in conducting a review more akin to a full systemic review than a traditional rapid evidence review. As noted previously, ADA research is complex, fragmented, and vastly heterogeneous in method, content, and outcomes. This presents a unique set of challenges when designing a systematic review process. Drawing on and/or adapting strategies from existing mixed methods reviews in social policy provided the research teams with general guidelines, but such studies are limited in what they can offer to this specific research area. Through the rapid evidence process, the research team created a comprehensive methodology for conducting reviews in complex social policy areas which, although time consuming for the purpose of rapid evidence review, can now be used for future systematic reviews.

5.3. Knowledge Gaps and Next Directions for Research

To help direct future research and ensure the utility of the findings, the research team met with the ADA Expert Panel and the ADA National Network Centers to solicit feedback on the results of the rapid evidence review. The feedback was incorporated into this report prior to dissemination. Collaboration with key ADA stakeholders is a necessary step in the knowledge translation process to help confirm findings, discuss implications of the analysis for policy and practice, and inform the research topics and questions for the forthcoming full systematic reviews.

The research team has worked closely with both the Expert Panel and representatives of the ADA National Network to confirm the findings included in this report. The project team solicited feedback through multiple venues. First, the draft technical report was sent to the Expert Panel for members to review the preliminary findings. This initial feedback was conducted to verify the findings presented in this report and to identify potential research gaps. The Expert Panel was asked about whether the findings were representative of the research on the ADA's influence on knowledge, attitudes, or perceptions in employment. Additionally, representatives from each of the ADA National Network centers were asked to see if their practice and experience with the ADA had yielded either support for or conflicting accounts of the findings presented in this report. All of the stakeholders were asked if any findings seemed inconsistent with their research and or practice with the ADA. The feedback from both of these groups is woven throughout this report and was used to improve clarity in reporting findings and to confirm the face validity of the synthesis claims based on the various content experts’ knowledge of the ADA’s impact.

The feedback from various ADA stakeholders was also used to pinpoint potentially problematic findings. Two findings were identified as potentially inconsistent and meriting a closer review. These findings were both removed from the draft summative conclusions based on the suggestions of the Expert Panel. Together, these findings both represent knowledge gaps in the collated body of ADA research on knowledge, attitude, and perceptions of people with disabilities.

The first finding relates to employer perspectives and the perceived origin of one’s disability. Through the rapid evidence review process, we gathered a body of research suggesting that the origin of disability affects employer perceptions about the fairness and reasonableness of accommodation requests. The notion of origin of disability refers to how some impairment types are blamed on an individual as they are seen as causing their own disability (Carpenter, & Paetzold, 2013; Conyers, Boomer, & McMahon, 2005; Florey & Harrison, 2000; Hazer, & Bedell, 2000; Mitchell & Kovera, 2006; Roessler & Sumner, 1997; Slack, 1996; Styers & Shultz, 2009). This phenomenon has been observed in a multitude of studies across a range of research questions and study designs. However as one stakeholder noted, this conclusion should still be considered primarily anecdotal until there is a closer interrogation of study design, the types of disabilities being investigated, and an additional cross-comparative analysis with the broader body of research on employer attitudes (beyond the research specifically on the ADA). Similarly, some ADA research about employer biases and decisions do not typically reveal such inherent biases. As one study notes, the research tends to paint a “rosy” picture of attitudes where employers remain unlikely to report discriminatory practice even in anonymous research (Kaye, Jans, & Jones, 2011). This finding and related body of research presents a key area of inquiry that can be used to generate more specific findings in future research. There is an abundance of research investigating this aspect of attitudes towards people with disabilities. It is the research team’s suggestion that this represents an area of inquiry that would benefit from systematic review to bring conclusive evidence to this debate.

The second finding relates to knowledge about the ADA by people with disabilities. A possible rationale for disclosing one’s disability status is to obtain the benefits of the ADA such as reasonable accommodation. There is evidence to suggest that a person is more willing to disclose when they are aware of their legal rights and the benefits of the law. Conversely, there are accounts of people who are less aware of their ADA rights who in turn decide not to disclose (Goldberg, Killeen, & O’Day, 2005; Madaus, 2006 & 2008). This relationship has not been explored sufficiently to identify a correlation or direct relationship as there is no evidence testing one’s likelihood to disclose after obtaining ADA knowledge. After stakeholder feedback, it was decided that the existing research on individual knowledge is an indicator that disclosure decisions are often weighed against the anticipated benefits. Until there is more longitudinal data or analysis across a wider body of people who have engaged with their ADA rights, it is not possible to ascertain if knowledge of the benefits afforded by the ADA is a contributing factor in disclosure decisions.

5.4 Next Steps

After discussing findings, the ADA stakeholders identified additional areas of interest for future research, including systematic reviews. The first priority identified was based on findings from this report. Multiple stakeholders note that persistent knowledge gaps exist about the disclosure process. Questions emerged such as: “What factors increase one’s likelihood to disclose for people with disabilities when trying to exercise their ADA rights? and, “Are certain groups of people with disabilities more likely to disclose in different scenarios (i.e. differing workplace, accommodation request etc.)?” Upon further discussion, such research questions were agreed upon as areas likely needing further inquiry, including a full and more substantive analysis of research specifically on disclosure. The subtopic of disclosure and its role on attitudes, knowledge, and perceptions was seen as pertinent to both additional systematic reviews and new research to more closely interrogate processes and practices to better inform people with disabilities about their ADA rights.

Further exploration of ways to respond to findings about barriers to ADA implementation identified in this research was a key suggestion by various expert practitioners involved with the ADA research. The findings related to stigma were agreed to be a key area of concern that requires additional attention in ADA research, advocacy, and practice. Multiple stakeholders also noted that additional research on techniques to change attitudes of employers and other stakeholders using the ADA would be useful. This suggestion is interconnected with the conclusion about how individuals often maintain a baseline level of knowledge in regards to ADA compliance.

Additional areas of inquiry were identified as priorities and suggestions made to guide the process for conducting future systematic reviews. Suggestions such as reporting a greater detail of research designs, study questions, and contradictory findings were useful to generate ideas of variables to explore during the full systematic review process. More specific inquiry and content exploration is now possible given the systematic process established during the rapid evidence review process. The various stakeholders also suggested a number of areas to generate summative and configurative conclusions using a similar methodological process that was presented during this stage of the review project. In particular, reviews that cross different topic areas that the ADA impacts are of particular interest. The intersectional impact of the ADA on healthcare and employment is one example of a systematic review area that was identified as topically important, and as an area with substantial fragmented research. Additionally, the stakeholders felt that a cross-sectional analysis of a priority sub-topic (such as attitudes, knowledge, and perceptions) could be explored across the full body of evidence. Finally, a review of the evidence on the ADA policy goals – equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency – was considered to be important. Each of these goals can be interpreted as a specific set of policy changes and indicators (see Silverstein, 1999 and NCD, 2007), which can be tracked in the existing evidence on the ADA. Future systematic reviews should therefore include contextual analysis of the findings in relation to these goals and the relevant indicators.

To meet these research priorities, the research team will begin the process of conducting full systemic review, expanding on the rapid evidence review process discussed here. This methodology adds an important new component to the field, as it identifies and consolidates a sample of existing ADA research on knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in the area of employment. It bears consideration that after almost twenty-five years of research on the ADA in general, we do not yet fully understand the legislative and cultural impact of this law. To help direct the systematic review of ADA research and to ensure the utility of the findings, the research team will continue to extensively collaborate with the ADA Expert Panel and other key national ADA stakeholders. This collaboration is an essential component of increasing knowledge translation of research, deepening our understanding of the impact of the ADA, and ultimately enhancing the protection of rights for people with disabilities.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1, 19-32.

Barbour, R. S., & Barbour, M. (2003). Evaluating and synthesizing qualitative research: the need to develop a distinctive approach. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 9(2), 179-186.

Baldridge, D. C., & Veiga, J. F. (2001). Toward a greater understanding of the willingness to request an accommodation: Can requesters' beliefs disable the Americans with Disabilities Act?. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 85-99.

Baldridge, D.C., & Veiga, J.F. (2006). The impact of anticipated social consequences on recurring disability accommodation requests. Journal of Management, 1, 158-179.

Blanck, P.D. (1996). Empirical study of the Americans with Disabilities Act: Employment issues from 1990 to 1994. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 1, 5-27.

Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C, Donovan, J, Morgan, M and Pill, R. (2002). Using meta-ethnography to synthesize qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, vol. 7(4), 209-215.

Bruyère, S.M. (1999). A comparison of the implementation of the employment provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) in the United States and the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995 in the United Kingdom. Cornell University Program on Employment and Disability / School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/

Carpenter, N.C., & Paetzold, R.L. (2013). An examination of factors influencing responses to requests for disability accommodations. Rehabilitation Psychology, 1, 18-27.

Chang, Y. (2010). A Systematic review and meta-ethnography of the qualitative literature: experiences of the menarche. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 447-460.

Conyers, L., Boomer, K., McMahon, B. (2005) Workplace discrimination and HIV/AIDS: The national EEOC ADA research project. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation. (1): 37-48.

Conyers, L., Unger, D., & Rumrill Jr., P.D. (2005). A comparison of equal employment opportunity commission case resolution patterns of people with HIV/AIDS and other disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 3, 171-178.

Cook, D., Meade, M. and Perry, A. 2001. Qualitative studies on the patient's experience of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest, 120: 469S-473S.

Davis, P. (2003) What is needed from research synthesis from a policy-making perspective? In. J. Popay (Ed.) Moving Beyond Effectiveness in Evidence Synthesis. Methodological issues in the synthesis of diverse sources of evidence (pp. 97-103). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., & Sutton, A. (2005). Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 10, 45-53.

Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., & Sutton, A.J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 1, 35.

Dowler, D.L., & Walls, R.T. (1996). Accommodating specific job functions for people with hearing impairments. Journal of rehabilitation, 3, 35.

Florey, A.T., & Harrison, D.A. (2000). Responses to informal accommodation requests from employees with disabilities: Multistudy evidence on willingness to comply. Academy of Management Journal, 2, 224-233.

Gerber, P.J., Batalo, C.G., & Achola, E.O. (2011). Learning disabilities and employment before and in the Americans with Disabilities Act era: Progress or a bridge too far? Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 3, 123-130.

Gilbride, D.D., Stensrud, R., & Connolly, M. (1992). Employers' concerns about the ADA: Implications and opportunities for rehabilitation counselors. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 3, 45-46.

Gioia, D, & Brekke, J.S. (2003). Rehab rounds: Use of the Americans with Disabilities Act by young adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 3, 302-304.

Goldberg, S.G., Killeen, M.B., & O'Day, B. (2005). The disclosure conundrum: How people with psychiatric disabilities navigate employment. Psychology Public Policy and Law, 3, 463-500.

Gordon, P.A., Feldman, D., Shipley, B., & Weiss, L. (1997). Employment issues and knowledge regarding ADA of persons with multiple sclerosis. The Journal of Rehabilitation, 63.

Graham, H., & McDermott, E. (2006). Qualitative research and the evidence base of policy insights from studies of teenage mothers in the UK. Journal of Social Policy, 1, 21-37.

Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. Journal of continuing education in the health professions, 26(1), 13-24.

Grant, M.J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91-108.

Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2011). An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publication Ltd.

Hazer, J.T., & Bedell, K.V. (2000). Effects of seeking accommodation and disability on preemployment evaluations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 6.

Hernandez, B., Keys, C., & Balcazar, F. (2000). Employer attitudes toward workers with disabilities and their ADA employment rights: A literature review - Americans with Disabilities Act. Journal of Rehabilitation, 4, 4-16.

Hernandez, B., Keys, C.B, & Balcazar, F.E. (2004). Disability rights: Attitudes of private and public sector representatives. Journal of Rehabilitation, 1, 28-37.

Houtenville, A., & Kalargyrou, V. (2012). People with disabilities: Employers' perspectives on recruitment practices, strategies, and challenges in leisure and hospitality. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 1, 40.

Jesson, J., Matheson , L., & Lacey, F. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Kaye, H.S., Jans, L.H., & Jones, E.C. (2011). Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 4, 526-536.

Kissam, P. C. (1988). The Evaluation of Legal Scholarship. Wash. L. Rev., 63, 221-1087.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. Retrieved from http://www.implementationscience.com/ content/ pdf/ 1748-5908-5-69.pdf

Lewis, A.N., McMahon B.T., West S.L., Armstrong A.J., & Belongia L. (2005). Workplace discrimination and asthma: The national EEOC ADA research project. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 3, 189-195.

MacDonald-Wilson, K.L., Rogers, E.S., & Massaro, J. (2003). Identifying relationships between functional limitations, job accommodations, and demographic characteristics of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 1, 15-24.

Madaus, J.W. (2006). Improving the transition to career for college students with learning disabilities: Suggestions from graduates. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 1, 85-93.

Madaus, J.W. (2008). Employment self-disclosure rates and rationales of university graduates with learning disabilities. Journal of learning disabilities, 4, 291-299.

Matt, S.B. (2008). Nurses with disabilities: Self-reported experiences as hospital employees. Qualitative health research, 11, 1524-1535.

McMahon, B.T., Shaw, L.R., West, S., & Waid-Ebbs, K. (2005). Workplace discrimination and spinal cord injury: The national EEOC ADA research project. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 3, 155-162.

McMahon, B.T., Rumrill Jr., P.D., Roessler, R., Hurley, J.E., West, S.L., Chan, F., & Carlson, L. (2008). Hiring discrimination against people with disabilities under the ADA: Characteristics of employers. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2, 112-121.

Mitchell, T.L., & Kovera, M.B. (2006). The effects of attribution of responsibility and work history on perceptions of reasonable accommodations. Law and human behavior, 6, 733-48.

Moore, D.P., Moore, J.W., & Moore, J.L. (2007). After fifteen years: The response of small businesses to the Americans with Disabilities Act. Work (Reading, Mass.), 2, 113-26.

Moss, K., Swanson, J., Ullman, M., Burris, S. (2002). Mediation of employment discrimination disputes involving persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 8, 988-994.

Nachreiner, N.M., Dagher, R.K., McGovern, P.M., Baker, B.A., Alexander, B.H., & Gerberich, S.G. (2007). Successful return to work for cancer survivors. AAOHN Journal, 7, 290-295.

National Council on Disability. (2007). The impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act: Assessing the progress toward achieving the goals of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Retrieved from http://www.ncd.gov/publications/2007/07262007

National Organization on Disability (2010). The ADA, 20 years later. Retrieved from http://www.advancingstates.org/sites/nasuad/files/hcbs/files/195/9739/surveyresults.pdf

Neath, J., Roessler, R.T., McMahon, B.T., & Rumrill, P.D. (2007). Patterns in perceived employment discrimination for adults with multiple sclerosis. Work: A Journal of prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation, 3, 255-274.

O’Day, B. (1998). Barriers for people with multiple sclerosis who want to work: A qualitative study. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 12(3), 139-146.

Paterson, B. L., Thorne, S., & Dewis, M. (1998). Adapting to and managing diabetes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 30 (1), 57-62.

Popovich, P.M., Scherbaum, C.A., Scherbaum, K.L., & Polinko, N. (2003). The assessment of attitudes toward individuals with disabilities in the workplace. Journal of Psychology, 2, 163-77.

Price, L., Gerber P.J., & Mulligan, R. (2003). The Americans with Disabilities Act and adults with learning disabilities as employees. Remedial & Special Education, 6, 350-358.

Robert, P.M., & Harlan, S.L. (2006). Mechanisms of disability discrimination in large bureaucratic organizations: Ascriptive inequalities in the workplace. Sociological Quarterly, 4, 599-630.

Roessler, R.T., & Sumner, G. (1997). Employer opinions about accommodating employees with chronic illnesses. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 3, 29-34.

Rumrill, P.J., Roessler, R.T., Battersby-Longden, J.C., & Schuyler B.R. (1998). Situational assessment of the accommodation needs of employees who are visually impaired. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 1, 42-54.