(Printer-friendly PDF version - 614 KB)

AUTHORS:

Department of Disability & Human Development

University of Illinois at Chicago

Sarah Parker Harris, Principal Investigator

Robert Gould, Project Coordinator

Anne Bowers, Research Assistant

Glenn Fujiura, Co-Investigator

Robin Jones, Co-Investigator

January, 2017

Funded by NIDILRR Project #90DP0015

SECTION 1: BACKGROUND AND PROJECT OVERVIEW

1.1 Overview of the ADA KT project

1.2 ADA KT project expert panel

SECTION 2: PROCESS AND METHODS

3.1 Application of ADA knowledge

3.2: implementation in health care setting

SECTION 4: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

4.1 Closing ADA information Gaps (‘Knowledge about knowledge’)

4.2 Advancing understanding of access

Appendix 1 ADA Health Care Literature Extracted Data

Evidence on the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) spans across a wide range of resources and is often considered to yield a range of conflicting results. More than 26 years following the ADA’s signing, there is still considerable need to consolidate the broad body of evidence to improve understanding about progress towards its intended goals. To address this need, the University of Illinois at Chicago is conducting a five-year multi-stage systematic review of the ADA as part of the NIDILRR funded National ADA Knowledge Translation Center based at the University of Washington. The project includes a scoping review, a rapid evidence review, and systematic reviews. This report provides a summary of the progress and findings from the final year of the project.

The review was conducted to generate a descriptive synthesis of the evidence to inform civil rights and public health policy, and to guide future research. ADA evidence in relation to health care access emerged as a priority topic for analysis following a scoping review and ensuing feedback from a panel of ADA experts. This report describes a systematic review and assessment of evidence on the ADA’s impact on health services and care access. The research question considered in this report is: What evidence exists that the ADA has influenced the accessibility of health care settings and practices?

The systematic review of ADA research on health care delivery and access entailed:

- Searching approximately 34,599 academic and grey literature records using the key search terms “Americans Disabilities Act” (and the appropriate delimiters).

- Examining and categorizing 461 ADA research records across a variety of topics.

- Reviewing and appraising records that were published after 1990, include the collection or collation of ADA research, and state a research question, purpose or analytical framework specifically about the ADA and health care.

- Appraising the literature to ensure that it adhered to a minimum level of reporting and also to ensure that each record including findings relevant to the research question.

- Conducting a thematic analysis of results across research to develop a summative overview of findings and assessment on the current state of ADA research on health care access from the last 26 years.

Highlights of the Report

- 54 articles relevant to the ADA and health care access were identified. 20 records were included in the final review that met the minimum standards of report for inclusion for analysis.

- Four non-mutually exclusive themes, or categories, of research were identified during the review. Eight of the ADA and health care records related to ADA knowledge. Eight of the included records contained evidence about compliance. Three records related primarily to implementation, and three records related to the experience of patients with disabilities. Key findings related to these themes include the following:

- Improving knowledge of the ADA amongst clinician and administrators is framed as the first step, and is often the most essential part of achieving the ADA’s implementation.

- Patient experiences are shaped by familiarity with the ADA’s scope and purpose. Adverse experiences are sometimes related to patients themselves misunderstanding key ADA information.

- Compliance is overwhelmingly studied as an issue of physical accessibility. There is limited knowledge to date on how more complicated forms of access are achieved in practice.

- The ADA is not thought of as the sole, or even primary, legislative tool to advance health care access for people with disabilities. Interconnected policy barriers are frequently discussed as access barriers.

1.1 OVERVIEW of the ADA KT project

The systematic review of ADA health care research was conducted as part of the final stage of a three-part five-year grant project funded by NIDILRR to systematically review the broad range of social science research on the ADA. The project is part of the National ADA Knowledge Translation Center Project and was created in response to the call to “increase the use of available ADA-related research findings to inform behavior, practices, or policies that improve equal access in society for individuals with disabilities” (NIDRR, 2011). The UIC project addresses the call by undertaking a series of reviews of the current state of ADA-related research and translating findings into plain language summaries for policymakers, technical reports, publications in peer-review journals, and presentations at national conferences. The review process is being conducted across three different stages: (1) a scoping review of the full body of ADA research, (2) a rapid evidence review that responds to key findings from the scoping review and provides a template for future review, and (3) a systematic review to synthesize research and answer specific key questions in the identified research areas. A complete project overview, as well as our previous technical reports are available at: http://adata.org/national-ada-systematic-review. We will use these reviews and syntheses to create a foundation of knowledge, inform subsequent policy, research and information dissemination, and contribute to the overall capacity building efforts of ADA Regional Centers.

1.2 ADA KT project expert panel

The need for a review of ADA health care research was largely informed by stakeholder input. The team has convened an expert panel of ADA stakeholders involved in research and technical assistance that provide feedback and guidance on review topics and materials. The project team also receives periodic feedback from representatives of the ADA National Network. Directors and other representatives of the ADA National Network provide feedback through their role on the KT committee for the larger ADA Knowledge Translation Center. Representatives from this committee provide periodic reviews through telephone conferences and in person presentations. Representatives are asked to comment on research findings, suggest directions in research, and help identify hard-to-reach sources yearly as part of the ADA National Network meeting.

Content experts from this group play a role in confirming the face validity of initial themes that were identified as pertinent policy areas and thematic evidence to begin categorizing the ADA research. The ADA expert panel and representatives from the ADA National Network are asked to review the findings to confirm practice-based suggestions and note potential gaps in research. Their on-the-ground perspectives are essential for noticing potential inconsistencies where research findings do not necessarily reflect anecdotal evidence or observations from common practices. Identifying inconsistencies helps to validate findings, and also suggest further research. The stakeholder review process is used to further refine suggestions for additional research needs and goals for the future systematic review of ADA research.

Research on the ADA’s influence on health care was identified as a priority for this project following the review of our last technical report. The immediate need was suggested due to ongoing issues and changes in legislation and practice that have placed health care access for people with disabilities at a critical juncture in both federal and state policy. It was suggested that further clarity about the ADA’s legacy in this area can assist in the future implementation of civil rights based law and policy in health care settings. It can also provide summative assessment of existing implementation research to suggest lessons learned from the literature.

1.3 purpose of the research

It is well documented that Americans with disabilities experience substantive barriers to health care. While debates regarding the specific impact of the ADA in the area of health care access continue, federal disability policy experts agree that the ADA has only limited impact on the delivery of health care to people with disabilities (Breslin & Yee, 2009). There are a number of limitations and caveats related to the ADA’s application in facilitating full and equal health care. For example, the ADA does not dictate enhanced or broader care coverage or access to health insurance for people with disabilities, nor does it require the provision of employer-provided health insurance. However, employers must provide equitable health insurance offerings to all employees, including individuals with disabilities and/or family members of individuals with disabilities, and cannot deny health care insurance to people with disabilities or those in relation to them. The significant lack of data collection and monitoring related to the ADA substantially contributes to its diminished impact on health care delivery and access. At the federal level, there are persistent calls to improve oversight and surveillance regarding ADA compliance in medical facilities and in health care systems (Peacock, Iezonni, and Harkin, 2015). Knowledge gaps about ADA implementation contribute to an overall poor understanding of how and if people with disabilities are accessing existing health care facilities and institutions.

By collating existing research, we will develop a better understanding of progress in implementing the ADA in the health care sector, and also establish baseline knowledge for future research and data collection to address known gaps. For research based in the social sciences, new sources of data related to health care access for people with disabilities may bring a wealth of information to improve knowledge and practice related to health disparities research. Furthermore, health care access data can be used to improve our knowledge base about the efficacy of past laws impacting full and equal access, such as the ADA.

The purpose of this review is to assess the current state of ADA health care evidence by consolidating, collating, and synthesizing the existing research. The review lays groundwork for future analytical comparisons and data collection to address knowledge gaps. The following research question was developed iteratively from a comprehensive scoping review on the full body of ADA research, and from the stakeholder feedback: What evidence exists that the ADA has influenced the accessibility of health care settings and practices? The remainder of this report describes the process and findings from the systematic review on the ADA’s influence on health care access, 26 years after the law’s passage.

2.1 Methodological Overview

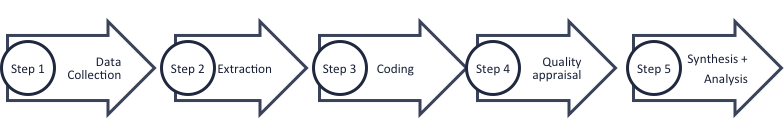

The research team built upon a synthesis technique that was developed through the ADA Knowledge Translation (ADAKT) Center Systematic Review project. Further detail on the process is available in our previous technical reports. The process and analytical framework is based on a scoping review that was conducted to consolidate the comprehensive body of ADA research (Parker Harris et al., 2014). The review process involves a technique called meta-ethnography to understand the breadth and depth of ADA research. Findings from multiple studies that shared similar categorical codes were grouped together to make interpretative synthesis arguments, or analytical statements describing shared conclusions generated from the reviewed research. The descriptive synthesis allowed for comparisons across the body of research and revealed what evidence exists to answer the central research question. The review was conducted in five stages to allow for a comprehensive and summative synthesis of the current state of ADA health care research (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Systematic Review Process

Data collection

During the scoping stage, an exploration of published and unpublished research was conducted through a keyword search for the term “Americans Disabilities Act” (and the appropriate delimiters) in the WorldCat library system (a search tool of frequently used and cited academic databases) and in the National Rehabilitation Information Center library database. Additional records were identified by supplementary searches, article recommendations from content experts, and backtracking of references. 34,599 records were initially screened at the abstract level, and then at full paper level if research questions, aims, or purposes were not stated in the introduction. Records were screened up until June 26, 2015 (the 25th anniversary of the ADA’s signing).

From this initial search, 461 ADA research records were found. Of the 461 ADA research records, 54 health care research records met the preliminary inclusion criteria for this review. Records included in this review are published after 1990, include the collection or collation of ADA research, and state a research question, purpose or analytical framework specifically about the ADA and health care. An initial appraisal was conducted to assess quality, and to ensure that the included research adhered to a minimum level of reporting and also to ensure that each record included findings relevant to the research question. 22 records were included in the final sample.

Figure 2. Decision tree of included records

.png)

Data extraction

Similar to other project reviews (refer to National ADA Systematic Review), the data extracted from final sample records included key study findings, suggestions for research, suggestions for policy or practice, and study limitations. The review includes this wide array of data to identify potential gaps in ADA information and to help craft suggestions for research. Ultimately, suggestions for future research and practice were derived from a mixture of evidence-based suggestions, our own gap analysis, and commentary from the panel of ADA stakeholders who routinely use ADA research and information and possess a heightened knowledge of needs and gaps (See Appendix 1 for a full overview of the data extracted from the included records).

Coding and Quality Appraisal

Similar to other project reviews (refer to National ADA Systematic Review), a thematic coding scheme was applied to identify prominent groups of research across the body of literature. First, a quality appraisal was conducted to ensure that studies meet a minimum standard for reporting research. Next, extracted data was reviewed and thematically coded to facilitate comparison and analysis. For example, the research questions and purpose were coded to identify the primary research topics of the included studies. Each of these categories of research is discussed further in the ‘Findings’ section.

Analysis and Synthesis

The analysis and review stage included a full review using a technique called meta-ethnography (Noblit & Hare, 1988). The process primarily involves three steps: looking at contradicting findings, findings repeated, and agreed upon findings, and ultimately producing a comprehensive interpretation of the research as a whole. The analytical process is intended to confirm knowledge about the current state of evidence and to create new knowledge by exploring the relationship of study findings between and across a diverse group of studies.

Four themes, or categories of research, emerged from the review of the literature. Each of these groups of research shared findings that are identified to assist in the synthesis process across studies (Campbell et al., 2003). The four different (non-mutually exclusive) categories were derived from coding the research questions of individual studies. The categories include: compliance, ADA knowledge, health care experience, and implementation.

Research Purpose of Included Research

|

Theme |

N |

% |

|

Compliance |

8 |

40% |

|

ADA Knowledge |

8 |

40% |

|

Implementation |

3 |

15% |

|

Experience |

3 |

15% |

|

Total |

22 |

(100%) |

The thematic categories were further categorized to identify the participant populations and/or information sources used in each study. Much of the included research used data collected from survey participants - thus the ‘participant population’ reflect the informants who participated in the research. Three different groups of informants were identified: medical practitioners, medical administrators, and people with disabilities. Other information sources included medical licensure and accreditation institutions (6 records) and measurements of the physical environment using the US Access Board’s ADA Accessibility Guidelines (4 records). Of the 22 included articles, 15 used quantitative methods (using a survey or evaluation), 5 used qualitative methods such as focus groups or interviews, and 2 studies used a mixture of methodological approaches.

The discussion that follows is used to explain the collective meaning of findings found across the different thematic categories research.

Across the literature, advancing knowledge of the ADA is framed as a necessary step to achieve full and successful implementation. General knowledge about the ADA’s purpose and policy guidelines is often limited to knowledge of physical accessibility. Health care professionals, academic professionals, and patients tend to describe their knowledge about the parameters of ADA policy as incomplete (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002; Grabois, Nosek & Rossi, 1999; Gronefeld & Koscielicki, 2003; Redick, McClain & Brown, 2000; Rose, 1999; Sanchez et al., 2000; Voss, Cesar, Tymus & Fiedler, 2002; Wasserbauer, 1996). There are similar concerns in specialist settings. For example, a national survey of psychiatric nurses demonstrated that they frequently do not have accurate information about the ADA and that many were unfamiliar with the basic facts and purpose of the policy (Wasserbauer, 1996). Most nurses within the study did not receive information from their state or other governance about ADA policy; those who did receive information (about half of the sample analyzed) received ADA policy information from their workplace, industry publications, or through a professional association membership (Wasserbauer, 1996). Likewise, occupational therapy (OT) professionals were found to have low levels of knowledge about provisions of the ADA such as requirements for public accommodations in businesses and commercial locations (Redick, McClain & Brown, 2000). Other studies reported similar findings regarding providers, specialists, and health professionals who were unfamiliar with the requirements of the ADA (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002; Grabois, Nosek & Rossi, 1999; Rose, 1999; Sanchez et al., 2000; Voss, Cesar, Tymus & Fiedler, 2002). Together, lack of knowledge of the ADA and its application to health care settings impedes the ability of health care workers to educate patients about the ADA and empower patients with disabilities to exercise their civil rights (Redick, McClain & Brown, 2000).

Knowledge barriers related to applying ADA information are linked to misunderstanding of individuals’ rights and responsibilities. To a lesser extent, overestimation of compliance in health care settings is also a barrier. Varied and often over-estimated descriptions of actual compliance with ADA physical accessibility standards were reported for general clinic managers as well as for substance abuse professionals and within radiology education programs (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002; Grabois, Nosek & Rossi, 1999; Gronefeld & Koscielicki, 2003; Rose, 1999; Sanchez et al., 2000; Voss, Cesar, Tymus & Fiedler, 2002). Overestimation may be an even greater issue as many health professionals do not understand how to apply the ADA to clinical settings. Physicians reported being uncertain of how to create accommodations for routine examinations (Grabois, Nosek & Rossi, 1999), and a survey of chiropractic clinics found that the perception of need and demand for accessible treatment facilities were minimized in this health care sector. Respondents assumed that building or facility owners were fully responsible for ADA implementation rather than the managers of the chiropractic clinics occupying these spaces (Rose, 1999). The pervasive misunderstanding of ADA policy and procedures indicates a need for a consistent directive regarding the purpose and boundaries of the ADA (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002).

Prominent policy figures have expressed general concern about the lack of disability civil rights knowledge amongst health practitioners (Peacock, Iezonni, and Harkin, 2015). Findings from the existing literature support the notion that barriers to ADA knowledge and understanding may be attributed to medical and other health care professionals receiving insufficient information about the ADA (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002; Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996; May, 2014; Pharr & Chino, 2013; Redick, McClain & Brown, 2000; Rose, 1999; Wasserbauer, 1996; Yee & Breslin, 2010). This information gap is an issue for general practitioners as well as for specialty clinicians. For example, many chiropractic clinics reported serving zero (0) clients with disabilities (Rose, 1999), thus theoretically negating their need for education regarding accessible facilities. Research has also shown that nurses reported having little experience sharing ADA information and advocating for patients with disabilities (Wasserbauer, 1996). However, one study found that an increase in ADA knowledge was predictive of decreased physical barriers in primary care offices (Pharr & Chino, 2013), and other research shows that both attitudes and knowledge about the disability improves with the implementation of ADA standards in the workplace (Redick, McClain & Brown, 2000). Thus, a rigorous dissemination of such policy information to all health care professionals could relieve pervasive uncertainty regarding the ADA (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002). Challenges remain for health care setting administrators to prioritize ADA implementation as long as policy information remains obscure (Yee & Breslin, 2010).

In this small body of literature, patient experiences are primarily analyzed in relation to knowledge and awareness of difference facets of the ADA. Notably, many patients themselves were found to be lacking in knowledge and awareness of ADA policy and methods of self advocacy (McClain, Medrano, Marcum & Schukar, 2000; Redick, McClain & Brown, 2000; Steinberg et al., 2006). For Stienberg et al. (2006), study participants identifying as deaf were limited in their understanding of the ADA and their legal rights, and were uninformed about self-advocacy skills in health care settings as well. Other research showed that ADA knowledge and its personal value and usefulness to individuals with disabilities varied across its sample frame, and the meaningfulness of the ADA was not consistent from participant to participant (McClain, Medrano, Marcum & Schukar, 2000). This policy knowledge gap and lack of self-advocacy could impact a patient’s self-efficacy and agency for personal preference and may also affect their degree of involvement in their own care.

Education and training are framed as the primary means to address knowledge gaps regarding ADA implementation. Studies reported a lack of training for medical professionals and health care administrators at various organizational leadership levels (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002; Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996; Pharr & Chino, 2013; Sanchez et al., 2000). Under-preparedness was reported in various aspects of medical practice including non-managerial levels, which suggests training needs are across all levels of the health care workforce (Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996; Pharr & Chino, 2013; Sanchez et al., 2000) and a call for increased professional training was also a theme within the literature included for analysis (Gordon, Lewandowski, Murphy & Dempsey, 2002; Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996; Pharr & Chino, 2013; Sanchez et al., 2000). The development of concrete industry standards for ADA implementation could also be pivotal for health care settings, as many primary and specialty physicians and other associated medical employees have no clear guidelines outlining best practices or accessibility requirements for the built environment and in-office medical equipment (Grabois, Nosek & Rossi, 1999; Yee & Breslin, 2010). The dissemination of such standards can be achieved through legislative or policy means (Yee & Breslin, 2010).

As a whole, the research primarily studied ADA compliance as an issue related to physical access and accessibility of the built environment. Similarly, health administrators and practitioners primarily understand ADA compliance as an issue of physical accessibility. A portion of the reviewed literature assessed the physical accessibility of provider offices, specialty clinics (such as chiropractic clinics), health care facilities (like substance abuse treatment facilities), and their surrounding public environments (Graham & Mann, 2008; Kirby et al., 1996; Mudrick & Schwartz, 2010; Rose, 1999; Sanchez et al., 2000; Voss, Cesar, Tymus & Fiedler, 2002). The degree of compliance with ADA guidelines varied widely between studies. Parking lot areas were the most commonly reported accessible feature of health care facilities (87% of the measured facilities according to Sanchez et al. [2000] and 84% according to Rose [1999]). Graham & Mann (2008) found that, on average, about 70% of practices could be considered “adequate” at meeting the accessibility guidelines of the ADA. Though some research found that most sampled health care locations were generally physically accessible (Rose, 1999), other locations such as hospital burn centers (Kirby et al., 1996) and substance abuse treatment facilities (Voss, Cesar, Tymus & Fiedler, 2002) had multiple reports of noncompliance. Buildings that were most accessible were more likely to have young and knowledgeable administrators (Pharr & Chino, 2013) and were more likely to have been constructed recently (Graham & Mann, 2008; Pharr & Chino, 2013). There is a variation in overall compliance in health care facilities, and also in perspectives regarding how to determine an accessible or adequate state of compliance.

Compliance beyond physical spaces is poorly understood, and research reports that implementation is underdeveloped in these areas. Other aspects of inaccessibility were related to in-office medical equipment (Graham & Mann, 2008; Mudrick & Schwartz, 2010; Sanchez et al., 2000), including adjustable examination tables and wheelchair accessible scales, and accessible restrooms (Graham & Mann, 2008; Kirby et al., 1996; Rose, 1999; Sanchez et al., 2000). The literature also revealed that failing to provide effective means of alternative communication, such as obtaining a sign-language interpreter, is a common accessibility problem in provider offices (Grabois, Nosek & Rossi, 1999; Rose, 1999) and reason for complaint by patients (Mudrick & Schwartz, 2010). Compliance with standards for physical spaces, medical equipment, and availability of alternative communication mediums should be weighed with equal importance when evaluating health care location accessibility under the ADA. Results of research on ADA noncompliance of provider locations may not improve until gaps in policy knowledge are addressed.

There is limited research on patient experiences specific to the ADA. The existing research primarily reports negative experiences with access in health care settings. Patient perspectives on the use of the ADA in health care settings were primarily discussed in relation to clinicians’ knowledge and communication. Perceptions of clinicians’ knowledge about the ADA seemingly play a role in the experience, as well as the actual accessibility features of different clinical settings. The literature analyzed reveals a number of positive (Steinberg et al., 2006) and negative (McClain, Medrano, Marcum & Schukar, 2000; Steinberg et al., 2006) experiences from people with disabilities regarding use of the ADA in health care settings. Indeed, there are a multitude of factors that are associated with overall negative experiences with the ADA in health care settings. Patients with disabilities reported negative experiences with their health care providers and facilities in terms of overall accessibility and interpersonal communication with clinicians, staff, and services available (McClain, Medrano, Marcum & Schukar, 2000; Steinberg et al., 2006). For deaf patients, difficulties in communicating with providers and staff are described as pervasive (Steinberg et al., 2006) as ASL interpreters were not always available. Another study reported patients with disabilities believed they were stuck ‘settling for less’ as they experienced physically inaccessible facilities and services within their local communities, including transportation (McClain, Medrano, Marcum & Schukar, 2000). Furthermore, health care experiences were characterized in terms of mistrust and frustration, with participants calling for increased education for providers about the sociocultural aspects of disability (in the case of this study, Deaf culture) (Steinberg et al., 2006). Positive experiences were also present in the literature, attributed to provider locations with experienced sign language interpreters and ASL-proficient doctors and staff for patients who are deaf (Steinberg et al., 2006). At this time, knowledge on patient experiences and use of the ADA in health care settings is scant.

Collectively, the themes discussed in the previous sections represent key areas in which health care access has evolved in the context of the ADA. In the final stage of the meta-synthesis process, an additional level of synthesis, is provided to develop overarching valuation about the research on the ADA’s influence on health care. The authors collaboratively generated the thematic findings by collating each author’s individual summative assessments of the literature, and developing interpretive higher order description until consensus was reached (Noblit & Hare, 1988). Two higher-order constructs emerged during the interpretation process. These findings are explained in relation to key ADA information gaps and steps to advancing understanding of access. Explanation of these findings is used to further address the research question, where evidence exists about the ADA’s influence in discourse, research, and practice.

In the reviewed research, increasing knowledge and familiarity with ADA information is framed as a critical component of applying the civil rights framework into practice. The research shows that ADA implementation gaps are largely attributed to knowledge and lack of information. Yet the research evidence about how knowledge is brokered and/or the prevalence of ADA knowledge in health care settings is incomplete. Simply put, medical professional ‘don’t know what they don’t know’. Together, the current state of knowledge suggests need for additional and more comprehensive inquiry into how ADA information is used and applied. These gaps are especially clear in relation to more complicated forms of access beyond physical compliance issues, such as those easily measured by tools as the ADA Accessibility Guidelines.

In the studies reviewed, a multitude of different health care administration offices were queried about their ADA knowledge and were also asked to assess the current state of implementation in the organizations where they worked. Responses were always characterized in terms of physical access, primarily referencing issues with features of observable accessibility (e.g. ramps and other entrance features), and at times considered barrier removal as a successful implementation strategy. As previously discussed, all of the different type of offices reported high accessibility, although the research reported lower compliance. Such research notes how there is an overstatement of success in ADA implementation efforts that is usually accompanied by individuals claiming confidence in interpreting the law into practice. Overstated compliance is a common finding throughout the ADA research where entities express strong intentions to comply, although such intentions are infrequently met (Parker Harris et al., 2014).

The research evidence establishes that health care practitioners and administrators often possess adequate understanding of basic compliance in provision of access, such as physical access to building entrances and exits (Drainoni et al., 2006). However, the ADA research on access does not provide definitive or notable conclusions about knowledge or compliance levels in relation to more complicated access issues (e.g. medical equipment or communication). That is not to say health care practitioners/administrators necessarily lack direct knowledge of their responsibilities under the ADA; rather, the research evidence to date is limited. This points to a gap in the ADA research evidence. The broader body of health care research overwhelmingly points to both a lack of understanding and application of more complicated forms of access (Kirschner, Breslin & Iezzoni, 2007). We do not know from the current body of ADA literature if structural access knowledge is a predictor of broader program access knowledge. The current state of ADA knowledge, and assumptions about its role in advancing health care access for people with disabilities, is inconclusive from the reviewed research.

Research regarding the impact of the ADA on alleviating access barriers has been mostly undertaken as a study of familiarity with the law and knowledge of physical accessibility guidelines related to provider office spaces and the built environment. Inaccessible health care features, and their presence and prevalence over the last 26 years in terms of structural, financial, and cultural/personal barriers, are well documented in the health care access field at large (Breslin & Yee, 2009; Peacock, Iezonni, and Harkin, 2015), but are not a part of the ADA literature. It is unclear if this inconsistency is indicative of policy limitation, or if it is just that ADA researchers have yet to analyze these more complex forms of access barriers. Pharr (2014) suggests the abundance of research and reporting of progress in physical access is because compliance with the physical accessibility requirements of a facility is easier to attain and measure than compliance with mandates for equitable program access. While policy knowledge of health professionals are identified as a possible predictive variable for physical accessibility compliance (Pharr & Chino, 2013), a comprehensive study of ADA provider knowledge and its relationship to accessibility beyond immediate physical environments or consumer satisfaction levels has yet to occur.

Reviewing the existing ADA research provides a partial assessment about how the ADA has shaped accessibility in health care settings for people with disabilities. Beyond problems related to the aforementioned information gaps, the research reveals interrelated problems in relation to the current state of ADA implementation and health care access. First, ADA health care research is under or even undeveloped in certain areas as the existing research has primarily relied on measures of physical access and structural accessibility as a proxy for full ADA implementation. The limited research has primarily been conducted to assess the legislation’s influence or effect on reducing and eliminating physical, tangible, and easily measurable barriers to health care for people with disabilities. Second, the existing research, although limited in its scope, does document knowledge and implementation gaps in even the most basic forms of accessibility, such as adherence to ADA standards and guidelines. Together, these two issues point to an imperfect evidence base and an unfinished state of ADA implementation – both of which are indicators of significant barriers to health care access for people with disabilities. Regardless of its statutory mandate, first person accounts from people with disabilities in health care settings continue to document significant access barriers that suggest deficiencies in meeting the ADA’s promise and spirit.

As knowledge about health care access in relation to civil rights expands through further academic inquiry, there is need for a more nuanced understanding of “access” than that which is currently provided in the existing research. Evaluating the effectiveness of the ADA requires simultaneous examination into multiple policy barriers at once. Various intersectional policy barriers may interact with or exacerbate one another, which can lead to worse health outcomes if access is not improved through legislative change (Neri & Kroll, 2003).

Across the research, there is agreement that the ADA is seldom the sole legislative tool that is drawn upon to facilitate access and accessibility. Frequently, areas of inquiry that impact health care access are framed beyond the legislative impact of the ADA. Studies of the practical and conceptual implications of the ADA illustrate the interconnected financial, legal, and policy aspects of implementation (Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996; Mudrick & Schwartz, 2010; Schroeder et al., 2009; Yee & Breslin, 2010). Especially as health care costs continue to rise, health care stakeholders are eager to understand how the policy affects organizational performance - a critical factor in determining if implementation may be posing an “undue burden” on institutions. Shortly after the ADA was signed into law, Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson and Mazzoni (1996) studied the financial impact of the policy for hospitals. ADA related accommodations provided by organizations for health care workers were found to be reasonably inexpensive. Forty-four percent (44%) of health care entities reported that job accommodations for hospital-based employees with disabilities cost less than $500 (Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996). While similar studies have been conducted about accommodations more generally (e.g., Job Accommodation Network, 2015), follow-up or replication studies have not been conducted specifically in health care settings.

Similarly, the ADA introduced new avenues of legal action for persons and employees with disabilities to exercise their rights. The previous study also found that nearly 20% of health care facilities received an employment or accessibility related complaint, and about 18% had an employment-related ADA legal matter (Jones, Watzlaf, Hobson & Mazzoni, 1996). Legal settlements from the ADA have affected both large and small health care entities as well as individual providers (Mudrick & Schwartz, 2010). ADA litigation has placed additional demands on organizations to provide accessible environments and equitable treatment to patients and employees or else they may, consequently, endure costly and time-consuming court cases (Mudrick & Schwartz, 2010). However, though complaints and litigation in response to ADA violations in health care settings can and do occur, such cases work to support fully accessible health care and employment environments for people with disabilities. The ADA compels the broader health care system to provide services and spaces free of accessibility barriers, although we have yet to see it implemented fully in this regard (Yee & Breslin, 2010).

Recommendations for research and policy reflect the iterative analysis of the research team and the collective synthesis of the findings and thematic analysis presented in this report. Preliminary findings were presented to the expert panel and representatives of the ADA National Network to assist in the process of validating findings and to gauge their application to current practice. The summary presented below is based on reviews from seven out of the ten regional centers, and five members of the expert panel. The primary purpose of the stakeholder feedback is to gauge to what extent reviewers agree that the research findings are representative of their experiences with the ADA and health care. Respondents largely agreed with the preliminary findings related to knowledge and information use, education and training, and compliance. Based on the panel feedback, two clarifications were made related to the limitations of the existing ADA evidence.

In relation to knowledge and Information use, most of the reviewers (10/12) agreed that general knowledge about the ADA’s purpose and policy guidelines is often limited to knowledge of physical accessibility. Lack of ADA knowledge is linked to misunderstanding of an individual’s rights and responsibilities. Findings from the included research suggested that health care administrators and practitioners tended to overestimate their knowledge of compliance efforts. The panel warned that this finding should not be generalized to explain the overall status of health care administrators and practitioners. Multiple reviewers noted that it much more common to work with entities that are not familiar with the law’s application. One reviewer noted that it unlikely that most practitioners are overstating their efforts because “not only are they are unaware of what is required, they also do not know whether or not they comply.” The evidence to date on the general knowledge of ADA is limited. Although research respondents tend to be more familiar with the physical access requirements of the law, the extent of knowledge of even the most basic facets of ADA compliance is unclear. Future research regarding the extent and prevalence of knowledge gaps can help to focus information and trailing efforts.

The panel agreed that there is limited research on patient experiences specific to the ADA in health care access. While the studies included in this review are primarily related to negative patient experiences with in-office medical equipment and communication access, they explained that such evidence is actually quite scarce. In the broader body of research, there is little evidence regarding prevalence or strategies to address problems with inaccessible medical equipment. The broader body of research on health care access is also a vital source of information to gauge how the larger goals of the ADA are being met, but similarly gives us a very limited understand of individual experiences with inaccessible health care facilities.

Lastly, reviewers were asked to identify main priorities for further research in the area of ADA and health care access. The suggestions primarily related to improving understanding about barriers and facilitators to ADA implementation in health care settings. Multiple reviewers noted the need to identify best practices, which includes identifying training and dissemination techniques, successful internal policies and procedures, and the extent to which credentialing bodies and professional organizations approach ADA and accessibility. One reviewer suggested the identification of model training programs for disseminating disability information for practitioners. Additional reviewer suggestions related to research needs are integrated into the final section of this report.

This review demonstrates the need for future research in three key areas:

1. The first area is related to ADA knowledge amongst medical professionals. Research to date does not tell us the extent to which medical professionals fully understand implementation of the law beyond basic compliance. More comprehensive ADA research is needed that includes information on program access, communication access, and consumer satisfaction. Concurrently, there is need for further work on increasing the publication and circulation of existing ADA information to health care professionals. More specifically, such knowledge could include updating accessibility standards and creating sufficient training and technical assistance opportunities for clinicians and employees in all health industry settings. Information dissemination alone is thought to be a weak intervention to address inaccessibility (Johnson, Brown, Harniss, & Schomer, 2010). Further technical assistance, follow-up, and clarity about the ADA’s goals and purpose can enhance dissemination efforts (Parker Harris et al. 2014).

2. The second research need is addressing the lack of experiential data related to use of the ADA in health care practice. The research need is not merely an issue of scarcity, but also reflects the wider body of disability health care research where stakeholder perspectives are increasingly valued as expert sources of knowledge to identify gaps in policy and health care provision (Kirschner, Breslin & Iezzoni, 2007). The broader body of health care access research that includes people with disabilities as key informants and stakeholders and inclusive participatory research methodologies is growing (Suarez-Balcazar & Hammel, 2015). Applied research centering on the experience of people with disabilities in relation to ADA application is still in its formative states. For example, only two studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review included perspectives of people with disabilities. The data to date is primarily observational, and generated from single-use surveys of compliance. Seven studies adapted the ADA Accessibility Guidelines or similar accessibly guidelines into a yes/no checklist of overall access. Research of this sort provides a cursory analysis of compliance issues, but is only a very partial aspect of reaching the ADA’s potential in health care settings. Further research that includes experiential accounts of individuals who have used the ADA in health care settings is necessary. There is a very small pool of information about how people with disabilities use civil rights or ADA information in health care settings. Advancing dissemination efforts related to exercising rights in health care settings, and follow-up inquiries regarding knowledge and understanding of the ADA, may be a starting point to inform this type of research. Additionally, qualitative accounts and other ways of documenting individual experiences and barriers to exercising one’s rights will be valuable sources of information to improve implementation. Moving forward, adding additional sources of information to the ADA research agenda such as experiential data will contextualize and explain our understanding of how studies of checklist items relate to greater program access. The primary recommendation at this time is for future research to collect and document user accounts regarding their experience with the ADA and other civil rights laws in health care settings. Ongoing efforts by advocacy organizations in this area (e.g. DREDF’s Health Care Stories initiatives) represent a valuable source of such information. More formal research to capture and assess the experiential accounts of people with disabilities can also enhance future implementation and policy changes as necessary.

3. Finally, there is a need for further research specifically on the ADA in health care settings that transcends issues of physical compliance. Some research gaps relate to provider experience and knowledge of complex forms of access, including communication access. It is recommended to enhance current information dissemination efforts by clarifying issues of implementation (providing a baseline understanding of the ADA) and following-up with more detailed technical assistance. In addition to information clarifying issues with ADA implementation, follow-up materials, and technical assistance, specifically addressing issues beyond physical access may also be beneficial to advancing implementation efforts.

Over the longer term, future research on the ADA in the domain of health care needs to examine the growing reach of civil rights legislation in the broader political context. Other federal laws, such as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), follow the ADA’s policy trajectory in expanding civil rights for people with disabilities in relation to health care coverage. The passage of the ACA expands the existing legislative toolbox and introduces a number of new policy measures to address disparities, inequality and inaccessibility. The ACA contains provisions that echo the promise of equal access and civil rights espoused in the ADA. The passage of the ACA immediately improved health care access for a number of individuals with disabilities who were previously rejected from health care coverage by eliminating “preexisting-condition” exclusions from eligibility and coverage. The ADA’s accessibility requirements impact a range of health care facilities and institutions, and also suggest a pathway for full and equal health care access for people with disabilities through its civil rights framework. The ADA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act both provide legislative guidance to address inaccessibility and discrimination in relation to health care access for people with disabilities.

It is reasonable to expect improved monitoring, knowledge, and research on the ADA and health care context in the near future. The ACA’s new monitoring and data collections requirements (Section 4302 of the ACA) represent one tangible step in social policy to better understand the impact of civil rights in practice, and to advance the current knowledge base on access to the health care system by people with disabilities. Civil rights still play a critical role in ensuring accessible health care for people with disabilities. Further research and data collection related to ADA information gaps can inform and advance implementation in health care settings. Twenty-six years after the signing of the ADA, knowledge gaps continue to mire implementation and efforts to better understand the social impact of the law. Continuing efforts to evaluate progress in implementation, especially as they relate to the key areas of missing information identified in this review, are critical to ensure accessible health care for people with disabilities, and to understand the full reach of the ADA.

Breslin, M. L., & Yee, S. (2009). The current state of health care for people with disabilities. Washington, DC: National Council on Disability.

Campbell, R., Pound, P., Pope, C., Britten, N., Pill, R., Morgan, M., & Donovan, J. (2003). Evaluating meta-ethnography: A synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Social Science & Medicine, 56(4), 671-684.

Drainoni, M. L., Lee-Hood, E., Tobias, C., Bachman, S. S., Andrew, J., & Maisels, L. (2006). Cross-disability experiences of barriers to health-care access consumer perspectives. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 17(2), 101-115.

Gordon, M., Lewandowski, L., Murphy, K., & Dempsey, K. (2002). ADA-based accommodations in higher education: A survey of clinicians about documentation requirements and diagnostic standards. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35(4), 357-363.

Grabois, E. W., Nosek, M. A., & Rossi, C. D. (1999). Accessibility of primary care physicians' offices for people with disabilities: An analysis of compliance with the Americans with disabilities act. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(1), 44-51.

Graham, C. L., & Mann, J. R. (2008). Accessibility of primary care physician practice sites in South Carolina for people with disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 1(4), 209-214.

Gronefeld, D. H., & Koscielicki, T. L. (2004). Radiography programs and the ADA. Radiologic Technology, 75(3), 187-196.

Johnson, K., Brown, P., Harniss, M., & Schomer, K. (2010). Knowledge translation in rehabilitation counseling. Rehabilitation Education, 24(3-4), 239-248.

Jones, D. L., Watzlaf, V. J., Hobson, D., & Mazzoni, J. (1996). Responses within nonfederal hospitals in Pennsylvania to the Americans with disabilities act of 1990. Physical Therapy, 76(1), 49-60.

Kirby, D. L., O'Keefe, J. S., Neal, J. G., Bentrem, D. J., & Edlich, R. F. (1996). Does the architectural design of burn centers comply with the Americans with disabilities act?. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 17(2), 156-160.

Kirschner, K. L., Breslin, M. L., & Iezzoni, L. I. (2007). Structural impairments that limit access to health care for patients with disabilities. JAMA, 297(10), 1121-1125.

May, K. A. (2014). Nursing faculty knowledge of the Americans with disabilities act. Nurse Educator, 39(5), 241-245.

McClain, L., Medrano, D., Marcum, M., & Schukar, J. (2000). A qualitative assessment of wheelchair users' experience with ADA compliance, physical barriers, and secondary health conditions. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 6(1), 99-118.

Moutsiakis, D., & Polisoto, T. (2010). Reassessing physical disability among graduating US medical students. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 89(11), 923-930.

Mudrick, N. R., & Schwartz, M. A. (2010). Health care under the ADA: A vision or a mirage?. Disability and Health Journal, 3(4), 233-239.

Neri, M. T., & Kroll, T. (2003). Understanding the consequences of access barriers to health care: Experiences of adults with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(2), 85-96.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Parker Harris, S., Gould, R., Ojok, P., Fujiura, G., Jones, R., & Olmsted, A. (2014). Scoping Review of the Americans with Disabilities Act: what research exists, and where do we go from here? Disability Studies Quarterly, 34(3): http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3883.

Peacock, G., Iezzoni, L. I., & Harkin, T. R. (2015). Health care for Americans with disabilities—25 years after the ADA. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(10), 892-893.

Persaud, D., & Leedom, C. L. (2002). The Americans with disabilities act: Effect on student admission and retention practices in California nursing schools. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(8), 349-352.

Pharr, J. R. (2014). Accommodations for patients with disabilities in primary care: A mixed methods study of practice administrators. Global Journal of Health Science, 6(1), 23-32.

Pharr, J., & Chino, M. (2013). Predicting barriers to primary care for patients with disabilities: A mixed methods study of practice administrators. Disability and Health Journal, 6(2), 116-123.

Polfliet, S. J. (2008). A national analysis of medical licensure applications. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 36(3), 369-374.

Redick, A. G., McClain, L., & Brown, C. (2000). Consumer empowerment through occupational therapy: The Americans with disabilities act title III. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54(2), 207-213.

Rose, K. A. (1999). A survey of the accessibility of chiropractic clinics to the disabled. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 22(8), 523-529.

Sanchez, J., Byfield, G., Brown, T. T., LaFavor, K., Murphy, D., & Laud, P. (2000). Perceived accessibility versus actual physical accessibility of healthcare facilities. Rehabilitation Nursing, 25(1), 6-9.

Schroeder, R., Brazeau, C. M., Zackin, F., Rovi, S., Dickey, J., Johnson, M. S., & Keller, S. E. (2009). Do state medical board applications violate the Americans with disabilities act?. Academic Medicine, 84(6), 776-781.

Steinberg, A. G., Barnett, S., Meador, H. E., Wiggins, E. A., & Zazove, P. (2006). Health care system accessibility. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(3), 260-266.

Suarez-Balcazar, Y., & Hammel, J. (2015). Scholarship of practice: Scholars, practitioners, and communities working together to promote participation and health. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 29(4), 347-351.

Voss, C., Cesar, K., Tymus, T., & Fiedler, I. (2002). Perceived versus actual physical accessibility of substance abuse treatment facilities. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 7(3), 47-55.

Wasserbauer, L. I. (1996). Psychiatric nurses' knowledge of the Americans with disabilities act. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 10(6), 328-334.

Yee, S., & Breslin, M. L. (2010). Achieving accessible health care for people with disabilities: Why the ADA is only part of the solution. Disability and Health Journal, 3(4), 253-261.

AppendiX 1 ADA Health Care Literature Extracted Data

|

Author/Year |

Research Purpose |

Theoretical Framework |

Research Participants |

Methodology |

Description of Methods |

Funding Sources |

Results |

Research Suggestions |

Policy/Practice Suggestions |

Limitations |

|

Gordon, M., Lewandowski, L., Murphy, K., & Dempsey, K. (2002) |

Determines extent of clinician understanding of ADA, documentation requirements, and diagnostic standards of the policy. |

None provided |

Clinicians (n=147; 85% psychologists, 15% other medical specialty) that submitted documentation for students seeking accommodations on a national exam administered for entrance into law school during 1998–1999 testing year (40% RR). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

Mean age of sample=50.3 years; mean years in practice=16.2. Survey asked demographics, professional degree information, and 27-item true/false quiz about ADA and educational accommodations. 40 survey retests conducted for reliability (score correlation=0.91; individual item agreement=0.94). |

No funding source provided |

•Average score was 75% correct; lack of consensus across sample indicates misunderstanding/uncertainty about ADA and guidelines for clinical practice. |

More research needed to survey other groups of clinicians; less ADA experience can expose critical knowledge gaps. |

•Increased practitioner awareness of ADA can reduce number of students seeking legal accommodations when solid rationale and appropriate documentation are unavailable. |

Participants may have had more ADA experience/knowledge than other clinician types. Response consensus may have been affected by working of survey items. |

|

Grabois E., Nosek, M., & Rossi, D. (1999) |

Assesses compliance with ADA and usability of physician offices for persons with physical and sensory disabilities. |

None provided |

General practitioners, family practitioners, internists, and obstetrician-gynecologists (n=62, 28% RR) |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

Survey of compliance with Title III mailed to stratified random sample of 220 primary care physicians with current practices in Harris County, Texas. Survey developed from DOJ portion of Code of Federal Regulations. |

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development |

•18% of responding physicians could not treat patients with disabilities in their clinics and were in violation of the ADA. 22% of physicians were improperly referring patients with disabilities to other clinics. |

Repeat study for larger response rate. |

•Need for DOJ standards on accessible furniture, office design, and equipment. |

Low response rate; many doctors reported not seeing any patients with physical disabilities and potential apprehension to admit office non-compliance is possible. |

|

Graham, C. L., & Mann, J. R. (2008) |

Assesses accessibility of PCP practices sites for people with mobility or sensory disabilities. |

None provided |

Primary care provider offices (n=68) in South Carolina. |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•PCP sites identified through two statewide networks. |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

•Accessibility varied across practices; average practice passed 70% of assessment items. |

Future studies could assess policies, procedures, and training of office staff on communication and accommodations for people with cognitive or mental health disabilities. |

•Primary care practices should make their practices fully accessible for all patients. |

Focus on offices in SC and cannot generalize findings to other locations or medical specialties. Participants are self-selecting so cannot know accessibility levels of non-participating practices. |

|

Gronefeld, D. H., & Koscielicki, T. L. (2003) |

Assesses familiarity with ADA among radiologic technology (RT) directors and examines information on program technical standards and student health assessments for ADA violations. |

None provided |

Radiologic technology (RT) directors in the United States (n=272, 44.7% RR) |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•RT directors/programs identified from Health Professions Career and Education Directory. |

Scholar Development Program grant from College of Professional Studies at Northern Kentucky University |

•Variation in interpretation/application of ADA among RT programs; majority of respondents found making accommodations for students was unnecessary (most common accommodation was for hearing impairments). |

None provided. |

•Admission criteria and procedures which give equal opportunity to all applicants should be established by RT directors. |

Sample only included programs accredited by JRCERT. Survey did not directly connect how physical exam was related to admissions process in each program. |

|

Jones, D. L., Watzlaf, V. J., Hobson, D., & Mazzoni, J. (1996) |

Describes responses of nonfederal hospitals to the ADA in terms of administration knowledge of ADA, organizational education and compliance, financial impact, and number of ADA-related complaints/lawsuits filed. |

None provided |

Chief administrators of non-federal hospitals in Pennsylvania licensed by the Pennsylvania Department of Health and Department of Public Welfare (n=117, 43.4% RR). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•23-item questionnaire mailed to chief hospital administrators asking about ADA provisions, efforts in organizational education and compliance, and financial and legal impact of ADA compliance. |

SHRS Research Development Fund, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Pittsburgh |

•Knowledge: High scores on ADA understanding (above 89% accuracy). Low scores on definition of disability (23.5% accuracy). |

Additional research could study regional or national differences in ADA compliance, examine the impact of ADA in private health care sector or from the perspectives of PWD, or perform longitudinal analysis to determine ADA impact. |

•Hospitals/providers should track ADA accommodation data. |

Results cannot be generalized to other hospitals/states. Survey respondents may not have been hospital administrators or made aware of all ADA-related activities at facilities. ADA-related complaints/lawsuits may not have been reported by respondents. Hospitals may not collect data on ADA compliance cost. |

|

Kirby, D. L., O'Keefe, J. S., Neal, J. G., Bentrem, D. J., & Edlich, R. F. (1996) |

Determines whether four hospitals with burn centers complied with Title III of the ADA. |

None provided |

4 unidentified hospital burn centers |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•Survey developed from ADA Accessibility Guidelines, used to inspect burn center facility and hospital common-areas. |

Texaco Foundation (White Plains NY) |

•All 4 burn centers had numerous architectural barriers for persons with disabilities, can be concluded they do not comply with Title III of the ADA. |

None provided. |

•Health Care Financing Administration certification process should require inspections of accessibility for ADA compliance (only signed assurance of compliance currently required). |

Limited sample size. |

|

May, K. A. (2014) |

Examines faculty knowledge of disability-related legislation and explores training opportunities faculty offered related to this subject. |

None provided |

Institutions identified as baccalaureate programs by the Pennsylvania State Board of Nursing (n=231, 26% RR). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•23-item online survey assesses knowledge of student requirements to receive accommodations, student and institutional responsibilities in providing accommodations, and examples of accommodations that may be requested. |

No funding source provided |

• Faculty member knowledge of ADA was low and could create barriers to student success. |

Research needed to differentiate specific issues related to clinical and classroom accommodations. Future research could examine validity of technical standards and the testing of strategies most conducive to accommodation. |

•Institutions should train/educate faculty about their responsibilities in providing accommodations. |

•Those unfamiliar with online surveys may have declined to participate. |

|

McClain, L., Medrano, D., Marcum, M., & Schukar, J. (2000) |

Determines perceptions and interpretations of wheelchair users about impact of physical and attitudinal barriers on accessibility of community goods and services, impact of the physical environment on social roles, and issues of isolation and secondary health conditions. |

Constructivism/Naturalistic Inquiry |

Adult wheelchair users (n=5). |

Qualitative - Individual Interviews |

• Informants recruited in a southwestern metropolitan community through personal contacts with local OTs. |

Disability and Health Program of the Public Health Division of the New Mexico Department of Health in cooperation with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

•Variation in participant ADA knowledge and value. ADA means little to some participants while others find the policy to have profound meaning. |

Further research needed in advocacy, education, surveillance, health promotion, and politics. “Settling for less” not found in previous study themes and more research is warranted in this area. |

•More accessible exercise facilities are needed to prevent occurrence of secondary conditions in PWD. |

•Study methods lacked optimal persistent contact with participants due to time constraints. |

|

Moutsiakis, D., & Polisoto, T. (2010) |

Assesses effect of ADA on the graduation of medical students with physical disabilities (MSPD) and the proportion of MSPD with disability identified before or after admission to medical school. |

None provided |

Deans of Student Affairs at accredited medical schools in the United States (n=51, 41% RR). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•Two-page questionnaire sent through mail and digitally from August 2007 to May 2008. |

No funding source provided |

•28 medical students (0.15% of total graduating medical students) with physical disabilities who graduated from 2002–2005. Proportion of graduating MSPD has significantly declined (compared to Wu et al. rate of 0.23%) (p=0.025). |

Future studies could explore trends in students with disabilities applying for admission to medical school. |

•Track progress of inclusion of MSPD on applications to increase medical school enrollment. |

Response rate of medical schools lower than previous study by Wu et al. Underreporting may be source of information bias. Recall bias possible if inaccurate records kept my medical schools. |

|

Mudrick, N. R., & Schwartz, M. A. (2010) |

Compares DOJ issues with ADA complaints/settlements in the last decade to the profile of health care access problems experienced by PWD. |

None provided |

Disability-related health care access concerns identified in research literature are compared to complaint settlements and major ADA lawsuits over the past decade. |

Descriptive (i.e. Theory/policy) |

•DOJ complaint resolution process events and relevant litigation records develop profile for how ADA has been used to address health care discrimination. |

No funding source provided |

•Not all health care access and discrimination issues reported by PWD have been a consistent focus of settled complaints/lawsuits. |

Future research to see if ADA should be better enforced or if policy should take other forms to address problems with health care access. |

• Health care provider settings should have effective accessible communication and eliminate any physical or programmatic barriers for PWD. |

•Difficult to measure magnitude of behavior change based on lawsuits. |

|

Persaud, D. & Leedom, C. L. (2002) |

Examines effect of ADA on admission and retention practices in nursing schools in terms of assessing and accommodating students with disabilities. |

None provided |

Nursing program directors of National League of Nursing (NLN)-accredited schools in California (n=52, 50% RR). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

• 6-part mailed questionnaire addressing: types of disabilities encountered and accommodations, examples of applicants/students with accommodation requests that could not be made, accommodations made that the institution did not feel were reasonable, accommodations made by institutions that would not be done again, and any on-campus services that help in making accommodations. |

No funding source provided |

•Nursing profession struggles with concepts of "essential functions" and "reasonable accommodations." |

Nursing instructors should explore and share accommodation methods that are reasonable and safe for students with disabilities. |

•Standardize program requirements so all individuals applying are fully informed of the expectations for entry/completion of educational program. |

•Disabilities may remain unknown if students fail or drop out. |

|

Pharr, J. (2014) |

Identifies ways US primary health care clinics provide PWD accommodations for structural barriers. |

None provided |

Primary care practice administrators that are members of a medical management organization (n=63, 73.3% RR). |

Mixed - Qual/Quant (Survey) |

•Online survey created using ADA construction guidelines, the ADA’s Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities, the Adaptive Environment Center’s Checklist for Existing Facilities, and relevant literature. •Eligible clinics included general practice clinics, family practice clinics, internal medicine, and OB-GYN clinics. •Survey questions asked demographics, accessibility of structures and equipment in clinic, and administrator knowledge of the ADA. Qualitative data from open-ended questions analyzed for major themes. |

No funding source provided |

•Methods of accommodations reported by participants were largely in violation of the ADA. |

Future research could explore if clinical staff (nurses/doctors) may have more knowledge regarding all aspects of a facility's accessibility. |

•Clinics should use acceptable alternative methods of accommodation when structural barriers are encountered during a health exam. Clinics should have proper accessible medical equipment for PWD, such as transfer lifts. |

Results not generalizable to specialty care clinics. Low participation rate subject to self-selection bias. Participant responses subject to self-reported information bias. |

|

Pharr, J., & Chino, M. (2013). |

Examines relationship between primary care practice administrators’ knowledge of the ADA and the number of accessibility barriers that patients with mobility disabilities might encounter. |

None provided |

Primary care practice administrators that are members of a medical management organization (n=63, 73.3% RR). |

Mixed - Qual/Quant (Survey) |

•Online survey created using ADA construction guidelines, ADA’s Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities, Adaptive Environment Center’s Checklist for Existing Facilities, and relevant literature. |

No funding source provided |

•Administrator ADA knowledge score (p=0.02), age of administrator (p=0.03), and buildings built before 1993 (p<0.01) were significant predictors of number of barriers reported at a practice location. |

Future studies should use methods which prevent sample self-selection to reveal more accurate results. |

•To reduce number of barriers to health care, comprehensive disability education needed to increase administrator knowledge of ADA and needs of PWD. |

Small sample size only suggests relationship between structural barriers and ADA knowledge of administrators, characteristics of administrators and characteristics of practices. Barriers experienced by patients with other disabilities (sensory and mental) not included in survey. Results not generalizable to specialty care clinics. |

|

Polfliet, S. J. (2008) |

Compares current (year 2006) practices of U.S. affiliated medical licensing boards asking applicants about mental health and substance use to application data from 1993, 1996, and 1998. |

None provided |

52 US affiliated medical licensing boards released initial registration applications and 50 boards released renewal applications for analysis in this study. |

Quantitative-Secondary data or analysis |

Initial & renewal licensure applications requested from 54 licensing boards from all 50 states. Each application examined for questions regarding applicant’s mental health/substance abuse history. Time and impairment qualifiers on applications from 2006 compared to applications from 1993, 1996, and 1998. |

No funding source provided |

•Medical board practices and professional licensure guidelines not aligned with court interpretations of ADA; many current application questions are potentially discriminatory. |

None given |

•Applications for licensure should not include questions relating to history of treatment or hospitalization for mental health or substance abuse as these do not reliably predict future risk to the public. |

Two licensing boards (Kansas and Puerto Rico) did not respond or refused to provide initial licensure application; four licensing boards refused release of renewal licensure applications. |

|

Redick, A. G., McClain, L., & Brown, C. (2000) |

Determines value of occupational therapist role in educating consumers about the ADA, knowledgeablility of ADA Title III, implementation of provisions, and empowerment of consumers who are wheelchair users in accessing public accommodations. |

Advocacy and Empowerment |

Occupational therapists that serve clients who are wheelchair users (n=152, 45% RR) |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

Survey originally mailed to 510 occupational therapists. 36-question survey was developed with items about demographics, ADA attitudes, knowledge of ADA Title III, activities in providing ADA Title III education, and the ADA resources used. |

Kansas Occupational Therapy Association |

•ADA accessibility knowledge mean score was 1.85/10 pts; reported actions to implement ADA provisions with clients mean score was 11.78/40 pts. |

Stratified random sample by state should be used in future research to increase geographically representative sample. |

•Low knowledge levels can affect independence and empowerment of wheelchair users. |

Low response rate from OTs. Sample comprised of AOTA members and findings may not be generalizable to non-AOTA members. |

|

Rose, K. A. (1999) |

Determines degree of ADA compliance in terms of accessibility for chiropractic clinics in two California counties. |

None provided |

Chiropractic clinics in Orange & Los Angeles counties (n=101, 50.5% RR). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

35-item surveys mailed to random sample of 200 chiropractic clinics in Los Angeles and Orange counties. Surveys asked about accessibility for chiropractic patients with disabilities, reasons for current access barriers, number of patients with disabilities currently being treated, and attitudes of providers and staff toward disability. Survey only covered patients that are deaf, blind, or wheelchair users. |

Los Angeles College of Chiropractic Research Department |

•46% of clinics did not treat any patients with disabilities. |

•Research needed on musculoskeletal disorders in the disabled population and if clients with these conditions respond to chiropractic care. |

•Education for chiropractors is needed regarding importance and means of ADA compliance. |

Survey not tested for reliability/validity. Low response rate to survey. Retrospective survey answers may be inaccurate. |

|

Sanchez, J., Byfield, G., Brown, T. T., LaFavor, K., Murphy, D., & Laud, P. (2000) |

Addresses clinic manager perception of accessibility compared to actual accessibility in health care clinics for persons using wheelchairs. |

None provided |

Health care clinics (n=40) in a Midwestern city. |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

•Random sample of clinics listed in telephone directory; clinics agreed to participate in a phone assessment and an on-site assessment for accessibility. |

Model Spinal Cord Injury System from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) |

•Variable compliance rate of sites meeting ADA guidelines. |

Future research could survey property owners or building managers to explore need for accessibility education and collaboration between owners and clinic lease-holders. |

•Educational information should be disseminated to clinics about increasing access to health care for people with SCI. |

Survey did not include all ADA Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities. Low response rate for the study. Facility compliance with ADA standards does not guarantee accessibility for all wheelchair users. |

|

Schroeder, R., Brazeau, C. M., Zackin, F., Rovi, S., Dickey, J., Johnson, M. S., & Keller, S. E. (2009) |

Determines whether medical licensing board application questions about an applicant’s mental or physical health or substance use history of the applicant are in violation of the ADA. |

None provided |