(Printer-friendly PDF version - 540 KB)

AUTHORS:

Department of Disability & Human Development

University of Illinois at Chicago

Sarah Parker Harris, Principal Investigator

Robert Gould, Project Coordinator

Anne Bowers, Research Assistant

Glenn Fujiura, Co-Investigator

Robin Jones, Co-Investigator

January 2017

Funded by NIDILRR Project #90DP0015

SECTION 1: BACKGROUND AND PROJECT OVERVIEW

1.1 OVERVIEW of the ADA KT project

SECTION 2: PROCESS AND METHODS

THEME 2: Role of disability service providers

THEME 3: Organizational culture and structure

THEME 4: Stigma and disclosure decisions

SECTION 4: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

From individual readiness to business needs

Appendix 1: ADA Disclosure Literature Extracted Data

Executive Summary

Evidence on the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) spans across a wide array of resources and is often considered to yield a range of conflicting results. Twenty-six years after the ADA’s signing, there is still considerable need to consolidate the broad body of evidence to improve understanding about progress towards its intended goals. To address this need, the University of Illinois at Chicago is conducting a five-year multi-stage systematic review of the ADA as part of the NIDILRR funded National ADA Knowledge Translation Center based at the University of Washington. The project includes a scoping review, a rapid evidence review, and systematic reviews. This report provides a summary of the progress and findings from one of the studies conducted in the final year of the project.

The following report contains a systematic review and assessment of research on the ADA and disclosure. The topic emerged as a priority for analysis following a scoping review and feedback from a panel of ADA experts. The panel suggested the topic to provide context to better understand recent changes to public policy that may impact disability disclosure and self-identification processes in work and other settings. The research question considered in this report is: What evidence exists regarding the application of ADA information to the disclosure process?

Evidence from this review can inform future research and policy related to disclosure and the use of ADA information in practice. The review entailed:

- Searching approximately 34,599 academic and grey literatures records using the key search terms “Americans Disabilities Act” (and the appropriate delimiters).

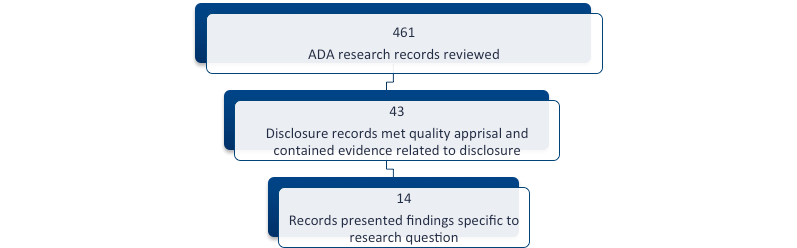

- Examining and categorizing 461 ADA research records across a variety of topics.

- Reviewing and appraising records that were published after 1990, include the collection or collation of ADA research, and state a research question, purpose or analytical framework specifically about the use of the ADA during the disclosure process.

- Appraising the literature to ensure that it adhered to a minimum level of reporting and also to ensure that each record included findings relevant to the research question.

- Conducting a thematic analysis of findings across research to develop a summative overview of findings and assessment on the current state of ADA research on the disclosure process from the last 26 years.

Highlights of the Report

- 43 articles related to the ADA and the disclosure process were identified. 14 records were included in the final review that met the minimum standards of reporting for inclusion and revealed information pertinent to the research question.

- Four non-mutually exclusive themes, or categories of research findings, were identified during the review. Findings related to information seeking, the role of service providers, organizational culture, and stigma.

- Across the research two primary research gaps are noted. First, existing evidence mostly pertains to disclosure as a matter of individual readiness rather than how it interacts with business needs. Second, research primarily documents the level of awareness about the disclosure process over other factors that may impact decisions to disclose. Knowledge gaps and suggestions for practice and research are discussed in relation to how ADA information is applied to the disclosure process.

1.1 OVERVIEW of the ADA KT Project

The systematic review of ADA disclosure research was conducted as part of the final stage of a three-part, five-year grant project funded by NIDILRR to systematically review the broad range of social science research on the ADA. The grant is being funded as part of the ADA National Network Knowledge Translation Center Project that was created in response to the call to “increase the use of available ADA-related research findings to inform behavior, practices, or policies that improve equal access in society for individuals with disabilities” (NIDRR, 2011). The UIC project addresses the call by undertaking a series of reviews of the current state of ADA-related research and translating findings into plain language summaries for policymakers, technical reports, publications in peer-review journals, and presentations at national conferences. The review process is being conducted across three different stages: (1) a scoping review of the full body of ADA research, (2) a rapid evidence review that provide that responds to key findings from the scoping review and provides a template for future review, and (3) a systematic review to synthesize research and answer specific key questions in the identified research areas. A complete project overview and previous technical reports are available at: http://adata.org/national-ada-systematic-review. We will use these reviews and syntheses to create a foundation of knowledge, inform the subsequent policy, research and information dissemination, and contribute to the overall capacity building efforts of ADA Regional Centers.

Research on the ADA and the disclosure process was identified as a priority for this project following the review of our last technical report. Stakeholders, including representatives of the ADA National Network and a panel of ADA experts, convened and identified a series of information gaps related to the disclosure process in the current policy context (see Parker Harris, Gould, Ojok, Fujiura, Jones, & Olmstead, 2014). A review of research related to the ADA and disclosure was identified as an immediate need. There are ongoing issues and changes in legislation that places the concepts of disclosure and the self-identification of disability at the forefront of national debates of policy and practice related to the employment of people with disabilities.

1.2 Purpose of this Research

Recent policy intended to promote affirmative hiring of people with disabilities has brought discussions of disclosure to the national stage. In March 2014, new rules to Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Vietnam Era Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act (VEVRAA) went into effect that require all federal contractors to set a goal for 7% of their workforce to comprise of people with disabilities. The updated regulations require businesses to take affirmative action to recruit, hire, promote and retain individuals with disabilities - and in doing so require employers to invite all job applicants to self-identify as a person with a disability for the purpose of the affirmative hiring initiatives. The self-identification process is used to track the utilization goal for federal contracts, and can be used to promote the hiring of people with disabilities to meet the goal.

The request for self-identification consequently impacts the way employers collect disability related information. All information related to disability and self-identification must be kept separately from personal records, and cannot be used for adverse employment decisions. The protection from discrimination aligns with policies and procedures for implementing the ADA. Disclosure is not required under the ADA. In the case of reasonable accommodations, disclosure may be required to make a disability-specific request (if the accommodation is routinely provided to other employees, disability disclosure may not be necessary). Furthermore, organizations must ensure that information obtained for affirmative hiring purposes is not used to discriminate or generate illegal and/or unwanted questions or conversation about one’s disability throughout the employment process. While the ADA, VEVRAA, and Section 503 all impact disclosure decisions, the process and rationale for disclosing under the different laws varies.

Information about the disclosure process is at the forefront of policy discussions and is of growing importance for technical assistance efforts. In the current policy context, there are a number of resources and training about the disclosure process. Despite the increase in proliferation of resources, knowledge gaps regarding ADA information continue to mire implementation. Efforts to increase the use and utility of ADA information are ongoing to address these gaps (see https://adata.org/ADAKTC). One central aspect of increasing ADA information use is consolidating the existing evidence. ADA information, however, is extremely diverse and is fragmented across a number of published and unpublished sources (Parker Harris et al., 2014). The evidence on disclosure is also diverse as decisions to disclose are impacted by a number of evolving factors such as personnel decisions, attitudes, organizational characteristics, and legal knowledge. Research on the disclosure process typically examines each of these factors individually. Consolidating the existing disclosure research can reveal a more complete picture of the different facets that impact the process.

This review is conducted to respond to stakeholder needs and address the ongoing need of consolidating evidence to improve ADA information use. This review addresses the question: What evidence exists regarding the application of ADA information to the disclosure process? The purpose of this review is to assess the current state of ADA evidence related to disclosure by consolidating, collating, and synthesizing the existing research. The review lays groundwork for future analytical comparisons and data collection to address knowledge gaps. This review, more specifically, provides a synthesized overview of evidence about the ADA and disclosure, 26 years after the law’s passage.

The research team built upon a synthesis technique that was developed through the ADA Knowledge Translation (ADAKT) Center Systematic Review project. Further detail on the process is available in previous technical reports. The process and analytical framework is based on a scoping review that was conducted to consolidate the comprehensive body of ADA research (Parker Harris et al., 2014). The review process involves a review technique called meta-ethnography to understand the breadth and depth of ADA research. Findings from multiple studies that share similar evidence were grouped together to make interpretative synthesis arguments, or analytical statements describing shared conclusions generated from the reviewed research. The descriptive synthesis allowed for comparisons across the body of research and revealed what evidence exists to answer the central research question. The review was conducted in five stages to allow for a comprehensive and summative synthesis of the current state of evidence on the ADA and disclosure (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Systematic Review Process

.png)

Data collection

During the scoping stage, an exploration of published and unpublished research was conducted through a keyword search for the terms “Americans Disabilities Act” (and the appropriate delimiters) in the WorldCat library system (a search tool of frequently used and cited academic databases) and in the National Rehabilitation Information Center library database. Additional records were identified by supplementary searches, article recommendations from content experts, and backtracking of references. 34,599 records were initially screened at the abstract level, and then at full paper level if research questions, aims, or purposes were not stated in the introduction. From this initial search, 461 ADA research records were found.

Records included in this review are published after 1990, include the collection or collation of ADA research, and state a research question, purpose, or analytical framework specifically about the ADA and disclosure. An initial appraisal was conducted to assess relevance to the research question, quality, and to ensure that the included research adhered to a minimum level of reporting and included findings relevant to the research question. Records were screened up until June 26, 2015 (the 25th anniversary of the ADA’s signing). Of the 461 ADA research records, 43 records met the preliminary inclusion criteria for this review.

29 of the 43 records were not used for this review because they did not contain information specific to the research question. 14 of the records contain findings specifically related to ADA information use. Much of the larger body of research related to disclosure at its periphery, such as in discussion of factors that impact accommodation decisions. Factors impacting the accommodation process are widely assessed in the literature already, and have been analyzed in our previous systematic review (Gould et al., 2015). The final studies contained evidence specifically about the ADA and the experience of disclosure and included discussion of factors impacting the disclosure process (see Figure 2). The included records present findings that explore disclosure in terms of the process of identifying as a person with a disability in order to exercise one’s rights under the ADA.

Figure 2. Decision Tree of Included Records

There are a multitude of studies on disability disclosure that may be related to the ADA. This synthesis seeks to build on existing reviews and the state of knowledge by looking specifically at the role of ADA information in the disclosure process. This synthesis should not be read as an exhaustive review of the ADA and disclosure, but rather a thematic analysis of how the ADA is used and applied during the disclosure process.

Data extraction

Similar to other project reviews (refer to /national-ada-systematic-review), the data extracted from final sample records included key study findings, suggestions for research, suggestions for policy or practice, and study limitations. The review includes this wide array of data to identify potential gaps in ADA information and to help craft suggestions for research. Ultimately, suggestions for future research and practice were derived from a mixture of evidence-based suggestions, our own gap analysis, and commentary from the panel of ADA stakeholders who routinely use ADA research and information and possess a heightened knowledge of needs and gaps (See Appendix 1 for a full overview of the data extracted from the included records).

Coding and Quality Appraisal

Similar to other project reviews (refer to /national-ada-systematic-review), a thematic coding scheme was applied to identify prominent groups of research across the body of literature. First, a quality appraisal was conducted to ensure that studies met a minimum standard for reporting research. Next, extracted data was reviewed and thematically coded to facilitate comparison and analysis. For example, the research questions and purpose were coded to identify the primary research topics of the included studies. Each of these categories of research is discussed further in the Findings section.

Analysis

A meta-ethnographic analysis was conducted (Noblit & Hare, 1988). The process involves three steps: looking at contradicting findings, findings repeated, and agreed upon findings, and ultimately producing a comprehensive interpretation of the research as a whole. The analytical process is intended to confirm knowledge about the current state of evidence and to create new knowledge by exploring the relationship of research findings between and across a diverse group of studies. Thematic findings within this subset of literature were then compared to the larger body of evidence of concurrent (agreeing) and discordant (contradicting) findings. Findings are discussed within the broader body of information related to disclosure. Face validity was confirmed by polling the expert panel and representatives of the ADA National Network. The discussion that follows is used to explain the collective meaning of findings across the different thematic categories of research.

Four themes, or second order constructs, emerged from the review of the literature. Second order constructs are shared characteristics of a group of findings that are identified to assist in the synthesis process across studies. Each of the constructs can be thought of as a schema, or categorizing detail, that explains the collective meaning of a group of findings found across research. The different (non-mutually exclusive) categories were derived from coding the research questions of individual studies, and iteratively creating categories to summate and describe the research. In exploring the research question, the research team identified four different areas of evidence related to the ADA and disclosure. The four areas include information seeking, the role of service providers, organization culture, and stigma.

The first area of evidence regarding the application of the ADA information to the disclosure process relates to information seeking – the process of how different individuals obtain information. The existing research on information seeking primarily relates to the type of information consulted, rather than the source. People with disabilities and service providers seek information that compares and contrasts the disclosure process at different stages of the job process; information about differences between the disclosure process in work and at school; and, literature that connects the concepts of disclosure, self-advocacy, and the promise of civil rights. There is little research evidence on how other entities covered by the ADA find information about disclosure.

The purpose for seeking disclosure information was primarily discussed in relation to preparing individuals for employment. Evidence of knowledge gaps amongst people with disabilities and other potential users of ADA information provides some context for the type of information sought by service providers and people with disabilities. ADA information gaps related to disclosure are thought to be systemic, where issues of disclosure and disability identity are rarely part of mandatory course work in higher education (Davison, O'Leary Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009; Parry, Rutherford, and Merrier, 2013). Parry, Rutherford, and Merrier (1996) first analyzed business school curricula and textbooks to assess the inclusion of disclosure in business communication classes. They found that 79% of instructors cover employment communication in courses taught, but only 45% covered disability disclosure in courses. Lack of coverage was found across all institutional types. None of the 13 most prevalent courses discussed disability disclosure. While 20 years have passed since this study, no replication or similar analysis of disclosure in business school curricula has been identified at this point.

Knowledge gaps are pervasive amongst people with disabilities as well. One of the primary concerns of service providers is that individuals with disabilities understand their rights and responsibilities as they transition from student to employees. The research, which primarily related to individuals with intellectual disabilities or learning disabilities, notes that the ADA is poorly understood in relation to the transition process (Frank & Bellini, 2005; Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003). Individuals with disabilities who report that they understand the ADA and disclosure well also perceive themselves to be better equipped for the job search process (Thompson & Dickey, 1994; Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003). ADA information is sought to assist in the job preparation process and to improve awareness of individual rights and responsibilities under the ADA.

Knowledge gaps are described differently throughout the research, but tend to focus on difficulties in applying information. Thompson and Dickey (1994) found that individuals with various disabilities often have a difficulty describing how they would be protected under the ADA. A number of studies identify ongoing information gaps and training needs of people with disabilities. For jobseekers with disabilities, questions about application of the ADA to disclosure often relate to the interview process. Research most often finds that individuals with disabilities are under-prepared for the disclosure process. Many individuals are simply unaware of their ADA rights (Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003; Scheid, 2005). Those that are aware of their rights may seek better information about disclosure but are often thought to be underprepared to apply their knowledge and actually exercise their rights (Frank & Bellini, 2005; Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003). Limited awareness of one’s rights under the ADA is widely considered a significant barrier to disclosure and reaching the full promise of the ADA.

There is some evidence about how to best convey information about disclosure and enhance awareness of the ADA’s legislative and social purpose. Information that breaks down disclosure decisions at different stages of the employment process is thought to be highly beneficial for individuals wanting to better understand the process. Researchers largely suggest that services providers need to be better prepared to assist individuals for disclosure scenarios during the pre-employment and interview stages (Davison, O'Leary, Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009; Florey & Harrison 2000). Service providers commonly suggest not to disclosure during the interview process, even if one is knowledgeable about their rights and responsibilities under the ADA (Bishop & Allen, 2001; Davison, O'Leary, Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009). Disability identity, however, is increasingly recognized as an important facet of individual identity and diversity, and can be seen as a strength during the interview process (Chan et al., 2010). The larger body of research and practice based guidelines largely suggests that individuals emphasize talking about individual capabilities over difficulties or inability to perform tasks (Hazer & Bedell, 2000). The evidence about how ADA information shapes or informs this process is limited, but overall shows that many people with disabilities only have a limited understanding of their rights and responsibilities in relation to disclosure.

Relatedly, researchers suggest that disclosure information should connect both the social goals of the ADA and the disclosure process. In the broader research on the ADA, information that conveys the legislative requirements and describes the goals of civil rights is more conducive to creating disability inclusive environments (Gould et al., 2015). There is evidence to suggest that hiring parties are more knowledgeable about policy and procedures related to disclosure rather than the social goal of inclusion that is suggested by the ADA (Baldridge & Veiga, 2006; Florey & Harrison 2000). When disclosure is primarily understood as a legal process to grant accommodations, it may dissuade requesting and granting accommodations (Baldridge & Veiga, 2001; Scheid, 2005). There is limited evidence about how ADA information is used to support the law’s social purpose, but evidence does show the potential detriment of understanding the ADA as just another piece of legislation.

The research on information seeking provides some cursory guidance regarding how ADA information can be constructed. Overall, training needs are most commonly discussed in relation to general knowledge levels of different groups, and less often discussed in terms of specific information needs (Parry, Rutherford, & Merrier, 1996; Scheid, 2005; Weber, Davis, & Sebastian, 2002). The broader body of knowledge translation research in the field of disability suggests that information dissemination alone is a weak intervention for instigating substantial policy change within organizations (Johnson & May, 2015). There is still need to better understand successful strategies for education and training dissemination beyond information dissemination. There is a plethora of evidence to suggest that the ADA is poorly understood in relation to the disclosure process by people with disabilities (Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003; Thompson & Dickey, 1994), service providers, (Bishop & Allen, C, 2001), and direct supervisors or managers (Parry, Rutherford, & Merrier, 1996; Weber, Davis, & Sebastian, 2002). The primary solution to improve understanding of the ADA discussed in the research to date involves service providers giving ongoing support and training to individuals with disabilities.

The second area of evidence regarding the application of ADA information to the disclosure process pertains to the role of disability services providers. Collaboration with outside entities, such as service providers, can better prepare individuals for workplace settings. The research discusses the roles of service providers in relation to facilitating individual preparedness, readiness, and ADA knowledge. There is little evidence related to the role of service providers in addressing demand-side characteristics, such as how disclosure is impacted by the needs of employers and the labor economy. Furthermore, the research focuses on the role of service providers specific to individuals with disabilities, and not for other entities involved in the disclosure process. For example, there is little evidence on how disclosure and ADA information is used in school and educational settings (Bishop and Allen, 2001). Assessments about the role of service providers in responding to business needs are even less common in the research (Davison, O'Leary, Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009). When employers do work with service providers, it is often for assistance in skill building or for guidance with different facets of ADA implementation such as providing reasonable accommodation (Davison, O'Leary, Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009; Frank & Bellini, 2005).

The role of service providers is primary analyzed in terms of preparing individuals with disabilities for disclosure as a facet of job readiness. Disability service providers provide education and information for individual with disabilities regarding stigma, disclosure decisions, and one’s rights under the ADA. Service providers are less prepared to provide guidance about the disclosure process in relation to business processes. For example, Bishop and Allen (2001) found that none of the 36 respondents (representing different Epilepsy Foundation affiliates) that were surveyed advised people with epilepsy to disclose their disability during the interview process. Only about half of the respondents suggested disclosure after being hired. Assessments of an individuals’ readiness typically involves assessing the overall knowledge or familiarity with the ADA amongst different groups of people with disabilities. Other qualitative research reveals that knowledge related to requesting accommodations is only one part of individual readiness. Some human resources professionals suggest that knowledge about when not to disclose is also a key aspect of understanding the ADA (Weber, Davis, & Sebastian, 2002). Overall, disability service providers are primarily seen as a resource to prepare individuals with disabilities for the disclosure process.

Although disability service providers may assist people with disabilities across a number of areas of daily living, the existing research primarily discusses the role of vocational rehabilitation and vocational services providers. The focus on vocational rehabilitation is partially explained by the existing sources of evidence. The majority of the research regarding ADA information use and disclosure comes from the field of rehabilitation. In this case, outside stakeholders are not typically consulted for legal guidance, but rather for their knowledge of broader disability related issues such as stigma and other factors impacting the disclose process (Bishop and Allen, 2001). Findings are often discussed in relation to improving the practice of case managers, support workers, and, to a lesser extent, technical assistance providers (Gerber & Price, 2003). While ADA technical assistance providers are often “gatekeepers” or “knowledge brokers” to ADA information of this sort (Fuijiura, Groll, & Jones, 2015), there is limited research to date related to their role in the disclosure process.

Notably missing from the analysis is the role of people with disabilities themselves in interacting with service providers. There is very limited evidence about how individuals with disabilities value or apply information from their frequent interactions with disability service providers. Researchers frequently note in their limitations or suggestions for further research to include people with disabilities to discuss their personal preferences and experiences with disability service provision (e.g., Davison, O'Leary Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009; Frank & Bellini, 2005). The studies that do query people with disabilities look at the knowledge level or overall “self-readiness” of people with disabilities in relation to disclosure (Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003; Snyder, Carmichael, Blackwell, Cleveland, & Thornton, 2010). Similar to the studies that query rehab providers, there is infrequently discussion of how such skills are applied in the workplace (Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003). Knowledge assessments tend to focus on individual skills, rather than how they might interact with business needs – or what are referred to as “demand-side factors” in the broader literature (Snyder, Carmichael, Blackwell, Cleveland, & Thornton, 2010). Together, these findings support the notion that there is considerable evidence about how service providers interact to train or educate people with disabilities. There is little information regarding how individuals use this information, or how service providers apply such information to meet business needs. This research gap is further analyzed in the discussion section of the paper.

The third area of evidence regarding the application of the ADA to the disclosure process relates to organizational culture and structure. Findings about ADA information, the disclosure process, and organizational culture largely come from studying employer attitudes. There is need for more diverse forms of evidence related to how entities develop inclusive policies, programs, and practices. ADA research tends not to detail organizational processes and how they impact the disclosure process.

Knowledge, or familiarity with the ADA, is an important facet of implementation for all involved entities to produce inclusive environments welcoming of disclosure. In the research, knowledge and familiarity with ADA information is thought to be an essential component of creating organizational cultures that are inclusive of people with disabilities (Weber, Davis, & Sebastian, 2002). Familiarity with ADA information is considered a vital aspect to facilitating an environment that welcomes disclosure, especially for individuals with limited exposure or social contact with people with disabilities (Davison, O'Leary, Schlosberg, & Bing, 2009). Low familiarity with the ADA amongst potential coworkers and hiring entities (e.g. managers, HR reps) is a known deterrent to disclosure after the hiring process (Price, Gerber, and Mulligan, 2003; Weber, Davis, & Sebastian, 2002).

Beyond the multitude of studies that assess ADA awareness amongst different groups, there is limited evidence regarding how knowledge is applied to and informs the disclosure process. Within the synthesized body of research, evidence regarding the disclosure process and organizational cultures is primarily discussed in terms of general attitudes about disability, knowledge about the ADA, and familiarity with people with disabilities or disability related issues (Baldridge & Veiga, 2006; Florey & Harrison 2000). Such findings provide context regarding how ADA information informs the disclosure process for representatives of human resources, managers and others involved in the personnel process. Developing an enhanced level of ADA understanding across all personnel, including potential coworkers with disabilities, is discussed as important for fostering an environment that is welcoming of disclosure (Snyder, Carmichael, Blackwell, Cleveland, & Thornton, 2010).

There is evidence to suggest that disability inclusive environments invite and welcome the disclosure of disability. Outside of the research to disclosure, there is a wide body of research related to how differing organizational processes support disability inclusion. Organizational missions, top-down policies, and programs that emphasize disability as an issue of diversity are factors that support the ADA’s goal of integration and full inclusion (Gould et al., 2015). “Organic supports” where individuals can receive assistance without filing formal accommodation requests are one facet of such programs that are thought to ease disclosure decisions (Florey & Harrison 2000). The characteristics of organizations seen as more welcoming to disclosure are thought to be similar to those of disability inclusive environments (Frank & Bellini, 2005). The evidence to date, however, is largely anecdotal and derived from single-application attitudinal surveys rather than applied examples or on the ground experience. The evidence on organizational culture and its relation to the disclosure process is limited and primarily understood in relation to the existing data on attitudes.

The fourth area of evidence regarding the application of the ADA to the disclosure process relates the concept of stigma. The research evidence suggests knowledge of the ADA (from individuals with disabilities, or the entities that they may disclose to) does not mitigate the impact of stigma on disclosure decisions. There are conflicting findings in the research on knowledge about the law and likelihood to disclose. Some research finds that having more knowledge about the law means that individuals are more likely to disclose. Other research finds that having more knowledge about the law means that individuals are less likely to disclose.

Stigma associated with disclosure makes the decision to exercise one’s rights personal and varies in different organizational contexts. Moreover, researchers increasingly suggest interpreting results with caution to recognize that in certain situations the decision to disclose is also indicative of a heightened awareness of one’s rights under the ADA (Scheid, 2005; Snyder, Carmichael, Blackwell, Cleveland, & Thornton, 2010). ADA information can be a conduit to individuals’ disclosure decisions when individuals feel confident in their knowledge of legal protections (Baldridge & Veiga, 2006; Florey & Harrison 2000). Increased ADA knowledge may also decrease the likelihood of disclosure, especially during the hiring process where discrimination is most difficult to prove (Dalgin & Bellini, 2008). Somewhat surprisingly, ADA information is seldom considered a factor that enhances people with “invisible” or “hidden disabilities”’ likeliness to disclose, especially for people with mental illness (Dalgin & Bellini, 2008; Scheid, 2005). This finding may partially be explained by the framing of the included research. The ADA research largely focuses on barriers to disclosure, and less on how people have used rights-based information to achieve successful employment protection or outcomes. From the research, it is suggested that pertinent ADA information considers both the positive and negative potential for disclosure in relation the ADA.

Others suggest that issues of disclosure can be alleviated through improved information dissemination and translation (See Gould et al., 2015). Across the evidence, it is clear that the ADA’s goals are often misunderstood. People in charge of granting accommodation requests, including HR representatives, may not firmly grasp or believe in the civil rights framework or social goal behind the ADA (Weber, Davis, & Sebastian, 2002).

There is evidence to suggest that stigma often dissuades individuals from disclosing. Some interpret evidence of ongoing stigma to suggest against disclosing a disability and requesting accommodations until after the extension of a job offer if possible (Hazer and Bedell, 2000). Decisions not to disclose one’s disability are thought to be more related to the fear of being treated “unfairly,” rather than facing overtly discriminatory treatment (Scheid, 2005; Snyder, Carmichael, Blackwell, Cleveland, & Thornton, 2010). Previous experience with discrimination is one of the primary deterrents of future requests (Frank & Bellini, 2005). This finding likely relates to the notion that stigmatic attitudes and practices are not eliminated by knowledge of the ADA. There is evidence to suggest that disclosure during pre-employment screening may reduce applicant suitability (Hazer and Bedell, 2000). Researchers tend to suggest avoiding the disclosure process during the pre-employment and job search phase because of disability stigma (Bishop & Allen, 2001). Furthermore, HR representatives’ familiarity with the ADA is not shown to effect their perceptions of suitability of specific job applicants (Hazer and Bedell, 2000). Stigma remains a strong barrier to inclusion, and achieving the goals of the ADA.

Stigma continues to shape the way ADA information is interpreted and disseminated. The research on disclosure also suggests that intervention and ADA information is needed to support individuals with disabilities early on, before discriminatory practices occur. Frank and Bellini (2005), in their discussion of the barriers to accommodation for people with visual impairments, find that individuals who are inadequately prepared for the disclosure process before the job search and interview process encounter further barriers down the line with disclosure and accommodations. They find that individuals who have negative experiences when they first disclose (such as being denied an accommodation) prefer to avoid disclosure and the use of the ADA through formalized institutional processes and structures. This finding is supported by research that show that anticipated negative responses often dissuade individuals from requesting reasonable accommodations (Price, Gerber, & Mulligan, 2003; Scheid, 2005). Individual preparation and ADA knowledge alone do not sufficiently equip individuals with the tools to combat stigma. Still, there is a clear need to address information gaps, beginning with youth with disabilities. Individuals are often underprepared for the complicated task of exercising one’s rights and recognizing potentially discriminatory practices.

Collectively, the themes discussed in the previous sections represent four areas of evidence regarding the application of ADA information to the disclosure process. In the final stage of the meta-synthesis process, an additional level of synthesis, or third order interpretation, is provided to develop overarching valuation about the research on the ADA and disclosure. The authors collaboratively generated the third order constructs by collating each author’s individual summative assessments of the literature, and developing interpretive higher order description until consensus was reached. Two higher-order constructs emerged during the interpretation process which are outlined below. Following this, the research team sought feedback (summarized below) from the ADA National Network and expert panel to confirm findings and assist in identifying the priority areas for next steps in this area of research. The findings below reflect two suggestions of direction for future research and practice.

Across the four categories of evidence, the disclosure process is primarily discussed in relation to individual readiness. Evidence about ADA information usage primarily pertains to existing knowledge levels, which is used as a proxy for assessing individual job readiness. The role of service providers during the disclosure process is similarly discussed in terms of equipping individuals with sufficient information to make disclosure decisions. In relation to stigma, disclosure is again most studied in terms of an individual’s knowledge about the law. The focus of individual preparedness reflect a growing concern that disability and vocational services may overly focus on ‘‘supply-side’’ factors impacting employment such as job skill training and ignore demand characteristics (responding to specific business needs) when supporting individuals with disabilities in the labor market (e.g., Chan et al. 2010).

There is limited evidence to date about successful organizational practices and the use of ADA information. The vast majority of research to date in relation to the ADA has focused on employer or coworker attitudes towards the law or disability (Parker Harris et al, 2014; Karpur, VanLooy, Bruyere, 2014). While attitudinal research is nearly ubiquitous in studies of the ADA’s implementation, surprisingly few studies specifically look at attitudes and their relation to disclosure as a process. The attitudinal research is largely outcome focused in that research is conducted to track the prevalence of potentially discriminatory attitudes (e.g., Scheid, 2005) or estimating the likelihood of positive responses to disclosure decisions (e.g., Baldridge & Veiga, 2001; Baldridge & Veiga, 2006). Information on the disclosure process, however, is notably missing from this body of evidence as the research more commonly is analyzed in terms of likeliness to obtain employment outcomes (e.g. inclusive hiring practice). There is very limited data at this time describing processes that lead to the development of inclusive organizational cultures that welcome disclosure. These findings support recent recommendations to better understand processes related to advancing disability inclusive environments, rather than solely focusing on tracking outcomes (see, for example, Karpur, VanLooy, Bruyere, 2014).

There is also limited evidence regarding how ADA information is used during the disclosure process to advance business needs and also to meet the aspirational goals of the ADA. In relation to business needs, there is growing rhetoric that disability inclusion is good for business – both for businesses’ bottom lines and for the formal recognition of disability as part of organizational diversity. Policies such as section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act that reward affirmative hiring practice are indicative of the growing recognition of disability as diversity in law and practice. Although the ADA and Section 503 entail separate processes for both disclosure and self-identification, it is thought that fostering inclusive cultures and practices will support environments to ensure successful implementation of both. Furthermore, the ADA’s civil rights framework suggests fostering organizational cultures that promote disability inclusion. In the context of disability civil rights, social inclusion is thought to include welcoming and recognizing disability identity as a point of pride in the wider spectrum of diversity.

The evidence regarding the application of ADA information to disclosure decisions is extremely discordant. Disclosure decisions are highly situational and impacted by a multitude of factors. While a number of studies have tried to estimate the relationship between ADA knowledge level and one’s likeliness to disclosure, results are largely inconclusive. Findings do support the notion that ADA information alone does not seem to be a strong enough intervention to combat the pervasive stigma of disability. Studies of potentially stigmatic attitudes reveal mixed findings about the effect of ADA information, and most commonly show that ADA information alone does not deter stigmatic perceptions or practice (Gould et al., 2015). There is more widespread agreement that ADA information can be leveraged to promote full implementation when ADA information is framed as a way to avoid legal action.

While valued ADA information is thought to present context about why one would want to or not want to disclose at different times, there is also a need to provide clarifying information about the ADA’s relationship to other laws and the social message of the ADA. The spirit of the ADA, and the promise of civil rights, suggest that disability is a point of positive identity and pride. Accepting disability as a positive attribute of individual identity suggests a broader discourse and openness about disability in organizational settings. It has been suggested that knowledge about the ADA can also be used to avoid accommodations when ADA information is framed as a way of “avoiding litigation” or merely compliance (e.g., Bagenstos, 2006; Parker Harris et al., 2014). The research focuses on overall knowledge levels rather than assessing or exploring the process of how different stakeholders successfully apply principles of the ADA in practice. Collectively, this evidence suggests that assessing ADA knowledge does allow us to fully understand if and how entities are adhering to the principles and goals of the ADA.

The need for this review was informed by discussion with practitioners of ADA information as well as an ADA expert panel. Through a series of discussions and surveys, the panel helped to identify a number of research needs, information gaps, and research questions related to the ADA and disclosure. The review question was informed by these discussions, as well as the iterative coding process and collation of data. As a review of existing data, we explored information needs by pooling existing information but could only address questions for which there is existing evidence. The summary presented below is based on reviews from seven out of the ten regional centers, and five members of the expert panel. The primary purpose of stakeholder feedback is to gauge to what extent reviewers agree that the research findings are representative of their experiences with the ADA and disclosure. Reviewer comments were also used to clarify findings and suggestions included in this report. Based on the panel feedback, two priorities for future research were identified.

(1) The reviewers identified the need for a cumulative guide to inclusive strategies and practice with employment settings. It is suggested that there is still a definitive need to understand specific attributes of organizational cultures, climates, and structures that support disability inclusion. Reviewers agreed that there is need for more diverse forms of evidence related to how entities develop inclusive policies, programs, and practices. For example, there are many different strategies that companies are implementing in relation to the self-identification obligations of Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act. The new targets for the hiring of people with disabilities by federal contractors and agencies may promote disclosure in ways that existing research has not fully considered. Additional products and technical assistance tools related to improving organizational culture might also be useful sources of evidence in this area.

(2) Reviewers suggested the need for a comprehensive guide or tool that lists various implications associated with disclosure in different workplace settings. It is suggested a comprehensive guide would include the pros and cons of disclosure, and provide information about the different levels and degrees of disclosure. It would also carefully detail the nuances and differences of disclosure in different settings, and at different stages of the job process. Reviewers noted both the positive aspects of disclosure as well as potentially unanticipated and negative consequences. Largely, the reviewers suggest that evidence is most critical for people with disabilities to better understand their rights and responsibilities under the ADA.

Research to date has predominately evaluated the most appropriate methods and timings of disclosure during the application, interview, and hiring process; barriers that individuals with disabilities face in disclosing their disability in the workplace; and variations in disclosure decisions amongst people with different disabilities, such as physical and psychiatric disabilities. What is missing from the current body of research is deeper interrogation into the broader socio-cultural factors that shape disclosure decisions. For example, we know very little about the organizational factors that better facilitate and support disclosure. Without considering such broader contextual factors, application of and knowledge about how to use ADA information becomes limited. Many people with disabilities still are hesitant to disclose. This finding holds true across a variety of organizational settings, including education and employment. However, issues of disclosure remain the forefront of ADA technical assistance and training. Entities covered by the ADA are increasingly seeking more complex information related to the disclosure process, and how other federal laws may impact individual rights and employer responsibilities. As new and frequent questions about disclosure are generated, there is a need to focus more predominately on the factors that impact how ADA information is used in the disclosure process. Without further research that includes examination of the broader organizational and factors, translation of research into practice becomes more challenging.

Moving forward, there is need for more nuanced and evidence-based research about the potential use of ADA information to address cultural understandings of disability, including mediating the negative impact of stigma. The research to date has overwhelmingly reported that stigma is the primary deterrent to disclosure in the workplace, and that negative attitudes and misunderstandings about disability shape the disclosure process in multiple ways. Research regarding stigma and disclosure is limited to identifying its existence, rather than providing directions for addressing it. New empirical sources of information are needed to better understand practices that promote not just disability diversity but disability inclusion. One potential source of information is to examine the practices of organizations that have had success in fostering disability inclusive environments. The evidence on where and how entities, namely businesses, receive ADA information is limited. Furthermore, there is a surprising dearth of direct evidence about how individuals apply information in practice. Such research would greatly assist in advancing our understanding of how to assess disability inclusion, as well as offer clearer evidence of what works in practice.

Bagenstos, S. R. (2006). The perversity of limited civil rights remedies: The case of abusive ADA litigation. UCLA Law Review, 54(1).

Baldridge, D. C., & Veiga, J. F. (2001). Toward a greater understanding of the willingness to request an accommodation: Can requesters' beliefs disable the Americans with disabilities act?. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 85-99.

Baldridge, D. C., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). The impact of anticipated social consequences on recurring disability accommodation requests. Journal of Management, 32(1), 158-179.

Bishop, M. L., & Allen, C. (2001). Employment concerns of people with epilepsy and the question of disclosure: Report of a survey of the epilepsy foundation. Epilepsy & Behavior, 2(5), 490-495.

Chan, F., Strauser, D., Maher, P., Lee, E. J., Jones, R., & Johnson, E. T. (2010). Demand-side factors related to employment of people with disabilities: a survey of employers in the Midwest region of the United States. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(4), 412-419.

Dalgin, R. S., & Bellini, J. (2008). Invisible disability disclosure in an employment interview: Impact on employers' hiring decisions and views of employability. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 52(1).

Davison, H., O'Leary, B., Schlosberg, J., & Bing, M. (2009). Don't ask and you shall not receive: Why future American workers with disabilities are reluctant to demand legally required accommodations. Journal of Workplace Rights, 14(1), 49-73.

Florey, A. T., & Harrison, D. A. (2000). Responses to informal accommodation requests from employees with disabilites: Multistudy evidence on willingness to comply. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 224-233.

Frank, J. J., & Bellini, J. (2005). Barriers to the accommodation request process of the Americans with disabilities act. Journal of Rehabilitation, 71(2), 28-39.

Fujiura, G. T., Groll, J., & Jones, R. (2015). Knowledge Utilization and ADA Technical Assistance Information. Journal of Rehabilitation, 81(2), 19.

Gerber, P. J., & Price, L. A. (2003). Persons with learning disabilities in the workplace: What we know so far in the Americans with Disabilities Act era. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 18(2), 132-136.

Gould, R., Parker Harris, S., Caldwell, K., Fujiura, G., Jones, R., Ojok, P., & Enriquez, K. P. (2015). Beyond the Law: A Review of Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions in ADA Employment Research. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(3).

Hazer, J. T., & Bedell, K. V. (2000). Effects of seeking accommodation and disability on preemployment evaluations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(6), 1201-1223.

Johnson, M. J., & May, C. R. (2015). Promoting professional behaviour change in healthcare: What interventions work, and why? A theory-led overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open, 5(9), e008592.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Parker Harris, S., Gould, R., Ojok, P., Fujiura, G., Jones, R., & Olmstead IV, A. (2014). Scoping Review of the Americans with Disabilities Act: What Research Exists, and Where do we go from Here?. Disability Studies Quarterly, 34(3).

Parry, L. E., Rutherford, L., & Merrier, P. A. (1996). Too little, too late: Are business schools falling behind the times?. Journal of Education for Business, 71(5), 293-299.

Price, L., Gerber, P. J., & Mulligan, R. (2003). The Americans with disabilities act and adults with learning disabilities as employees: The realities of the workplace. Remedial and Special Education, 24(6), 350-358.

Scheid, T. L. (2005). Stigma as a barrier to employment: Mental disability and the Americans with disabilities act. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 28(6), 670-690.

Snyder, L. A., Carmichael, J. S., Blackwell, L. V., Cleveland, J. N., & Thornton III, G. C. (2010). Perceptions of discrimination and justice among employees with disabilities. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 22(1), 5-19.

Thompson, A. R., & Dickey, K. D. (1994). Self-perceived job search skills of college students with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 37(4), 358-370.

Weber, P. S., Davis, E., & Sebastian, R. J. (2002). Mental health and the ADA: A focus group discussion with human resource practitioners. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 14(1), 45-55.

Appendix 1: ADA Disclosure Literature Extracted Data

|

Author(s) |

Theoretical framework |

Research purpose |

Sample |

Methods |

Procedure |

Funding Sources |

Results |

Future Research |

Policy & Practice |

Limitations |

|

Baldridge, D. C., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). The impact of anticipated social consequences on recurring disability accommodation requests. Journal of Management, 32(1), 158-179. |

Partial mediating-effects model of decision-making. |

The study measures the likelihood of employee accommodations request by developing and testing a decision-making model. |

Hearing-impaired employees (n=229, 33.3% RR) and an expert panel. |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

Variables were operationalized and Partial Mediating-Effects Model of decision-making was developed with expert panel. Web survey was distributed by email from hearing-impaired association and service directories. Variables analyzed included: monetary cost (IV), impositions on others (IV), likelihood of supervisory compliance (mediating), personal cost (mediating), normative appropriateness (mediating), and potential effectiveness of accommodation requested (control). 458 total scenarios involving 34 different recurring accommodations were tested for significance using logistic and linear regression analyses. |

U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children and Families and the Univ. of CT A.J. Pappanikou Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities Education, Research, and Service. |

Personal costs and imposition on others negatively affect the likelihood of an accommodation request being made by survey respondents. Personal costs and imposition negatively impact the assessment of the requester regarding normative appropriateness. These findings overall may have an overall negative influence on disability accommodation requests being made in the future. Supervisory compliance is a more significant mediator for imposition than monetary cost, indicating that accommodation requests are strongly influenced by relationships with supervisors and coworkers. The partial mediation model was supported. |

Future research could expand to non-disabled employees making requests in the workplace (such as for family program benefits, etc.). |

Managers and supervisors should understand that accommodations, and making requests for them, is not a simple or easy task. Managers should be aware of how organizational culture and interpersonal dynamics shape the accommodation request process. |

Survey response rate was low. Survey results are self-reported responses and may lack accuracy. There may be alternative explanations for the findings of the study. |

|

Baldridge, D. C., & Veiga, J. F. (2001). Toward a greater understanding of the willingness to request an accommodation: Can requesters' beliefs disable the Americans with disabilities act?. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 85-99. |

Theories of planned behavior, help-seeking, and distributive justice. |

The study proposes a framework predicting accommodation request likelihood based on salient beliefs shaped by situational characteristics. |

N/A |

Descriptive (Theory/policy) |

Researchers used the theories of planned behavior, help-seeking, and distributive justice to create an Accommodation Request Likelihood Framework. Situational characteristics identified included workplace attributes (accommodation culture), accommodation attributes (accommodation magnitude), and disability attributes (onset controllability). Salient belief formation by the requester characteristics included personal assessments (perceived accommodation usefulness, image cost, fairness, and compliance), and normative assessment (perceived appropriateness and social obligation). Situational characteristics shape salient beliefs; salient beliefs may influence the likelihood of accommodation request within the model. |

No funding source provided. |

The act of requesting accommodation is layered with situational factors which influence salient beliefs that impact the likelihood of accommodation request outcome; accommodation request-making is not easy and personal costs are often not considered. Policy which mandates right to accommodation may affect beliefs regarding public image. Requester beliefs have the power to undo the rights granted under the ADA if the process of accommodation request is negatively influenced by the beliefs of employees with disabilities. The model developed is effective for understanding accommodation request behavior in terms of specific disability groups and workplace contexts. |

Future research can explore the extent of each of the six salient beliefs and their interaction effects on accommodation request likelihood. Future studies can explore which salient beliefs are most influential in the decision factor (overall and at the individual level). The impact of inclusive organization culture should also be understood in terms of effect on salient beliefs. |

Organizations should embrace the ADA and truly desire to improve equality for people with disabilities. Supportive employment environments are critical; accommodations can improve work performance. Managers should be actively seeking accommodation solutions and assure requesting employees that they will be treated well. |

Extant theory and research cannot fully answer the practical questions raised by this research. |

|

Bishop, M. L., & Allen, C. (2001). Employment concerns of people with epilepsy and the question of disclosure: report of a survey of the epilepsy foundation. Epilepsy & Behavior, 2(5), 490-495. |

None given. |

Study reports survey results of EF employment assistance program affiliates about different employment-related concerns/questions from people with epilepsy & how EF affiliates advise people with epilepsy in terms of disclosing epilepsy status when seeking employment. |

Executive Directors of Epilepsy Foundation employment assistance program (JobTech) affiliates (n=36, 58% RR). |

Quantitative Research – Surveys |

Surveys sent by mail to 62 Epilepsy Foundation employment assistance organizational affiliates. Reminder mailings sent after 30 days. Survey asked about two major themes: different employment-related concerns/questions asked by people with epilepsy who have contacted the EF & how EF affiliates advise people with epilepsy regarding disclosing disability during the employment-seeking process. |

No funding source provided. |

Most frequent employment questions/concerns were: (1) questions about resources in finding a job, (2) questions about disclosure of epilepsy status in applying for a job, (3) reports of or questions about discrimination or ADA violations, (4) questions about the ADA, (5) questions about dealing with co-workers/ supervisors, (6) questions about the appropriateness of a particular position, and, (7) questions about drug testing in job application process. No respondents advised people with epilepsy to disclose on application or in an initial interview. 19 of 36 respondents advise people to disclose after being hired. 26 stated disclosure advice depends on the situation. |

Research about employment stigma and attitudes of employers about hiring people with epilepsy need further study. |

Frequently arising reports/questions about discrimination or ADA violations suggests need to continue education of employers and people with epilepsy about ADA and other employment-related laws. |

No randomization of survey response choices. Does not include input from people with epilepsy. Persons other than the executive director completed some of the surveys. Selection bias because only reporting outcomes for people who could/did call an EF affiliate for advice. |

|

Davison, H., O'Leary, B., Schlosberg, J., & Bing, M. (2009). Don't ask and you shall not receive: Why future American workers with disabilities are reluctant to demand legally required accommodations. Journal of Workplace Rights, 14(1), 49-73. |

Baldridge and Veiga’s (2001) framework - situational characteristics influence the formulation of a potential requester’s beliefs, which then influences likelihood of requesting an accommodation. |

Hypothesis 1: Personal assessments will mediate the relationship between perceived accommodation culture and accommodation request likelihood. Hypothesis 2: Past accommodation requests will be positively related to future accommodation request likelihood. Hypothesis 3: Past accommodation requests will be related to perceptions of accommodation culture. Hypothesis 4: Knowledge of the ADA will be positively related to future accommodation request likelihood. Hypothesis 5a: The majority of disabled individuals have not requested accommodations in the past. Hypothesis 5b: Disabled individuals will be unlikely to request accommodations in the future. |

University undergraduate/graduate students with disabilities (n=273), 89 respondents with disabilities (answered Qs about accommodations) included for analysis. |

Quantitative Research – Surveys |

Online survey was developed to determine disability status and to assess perceptions of university culture and personal assessments. Survey scales included disability status, perceived accommodation culture, personal assessments, accommodation requests, individual personal difference measures, knowledge of the ADA, and demographics. |

No funding source provided. |

The more helpful and supportive the university culture was perceived to be, the less concerned individuals were about requesting accommodations. The more concerned individuals were about requesting accommodations, the less likely they were to consider requesting future accommodations. Some personality traits (e.g., emotional stability, agreeableness) may indirectly influence accommodation request likelihood. Students that requested accommodation in the past were less likely to view the university culture favorably. Knowledge of ADA not related to likelihood of accommodation request, but is related to worse perceptions of university accommodation culture/support level. |

An analysis of circumstances in which certain accommodations are more/less effective. Develop organizational best practices in employee accommodations. |

Need to educate people with and without disabilities about the ADA. PWDs may need to educate employers about ADA, including suggesting accommodations and explaining how accommodating PWDs can benefit the entire organization. Provide employers with information about cost-effectiveness of accommodations. Universities and student groups should train students how to request accommodation in the future workplace. |

Results may not be generalizable to other settings. Survey scales developed using interviews with students from a different university than those students in the sample. |

|

Florey, A. T., & Harrison, D. A. (2000). Responses to informal accommodation requests from employees with disabilites: Multistudy evidence on willingness to comply. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 224-233. |

None given. |

The study seeks to identify how psychological characteristics of an employee with a disability requesting an accommodation, a manager receiving accommodation requests, and an accommodation request itself generate predictable outcomes. |

Managers that were recruited by undergraduate students in an introductory management class (n=114). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

Four vignettes were composed to represent each experimental condition. Participants were asked to respond to questions about their reactions to the reading. Levels of request magnitude (degree of personal resources) and levels of onset controllability (disability cause) were crossed in between-subjects design. Reactions were measured with Likert-scales of agreement and semantic differential scales of likelihood. Type of disability (hearing impairment) remained constant in vignettes to prevent confounding. |

No funding source provided. |

Managers accommodating someone "at fault" for their disability had more negative reactions. High-performance employees had greater manager compliance with accommodations. Accommodations that required more organizational resources received greater resistance. Previous disability contact was not significantly related to psychological responses to accommodation requests. Source and message characteristics highly influential on perceived fairness, performance instrumentality, attitude toward requests, and compliance obligation. Obligation neutralizer of the effects of attitudes. |

Research in the future can explore the effects of message and receiver characteristics, as well as other source characteristics that may influence outcomes. |

Organizational policies should facilitate appropriate responses to accommodation requests. Managers should understand that disability history for an employee may not be considered under the ADA and the employee’s added value to the organization should be highlighted. HR education should include a behavior-focused understanding of obstacles to request-making, such as unsupportive work environments and biased managerial attitudes. |

Validity of results from scenario-based experiments may be questionable. The study lacks hard data from behavioral observations. The relationships among attitude, obligation, and intention may be inflated due to method variance. |

|

Frank, J. J., & Bellini, J. (2005). Barriers to the accommodation request process of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Journal of Rehabilitation, 71(2), 28-39. |

Cites Greene's (2000) recommendation to use qualitative methods when evaluating social programs and policy. |

The study describes the difficulties blind/visually-impaired individuals encountered with the accommodation request process of the ADA in employment and other daily-living settings/situations. |

Persons who are blind or with significant visual impairment (n=20). |

Qualitative Research – Interviews |

Purposive sampling for participants, final sample of 12 men and 8 women (n=20) that are blind. In-depth and follow-up telephone interviews used a general interview guide with the order and wording not predetermined. Coded excerpts of each interview and the themes were reviewed by a panel of experts selected for their expertise in rehabilitation counseling/research. |

No funding source provided. |

ADA request process is ineffectual way of obtaining access to print as accommodation, participants described unexpected/critical risks when requesting. Five themes regarding barriers to requesting accommodation were found: (1) Broken Trust and Betrayal, (2) Multiplicity of Barriers, (3) Fear of Retaliation, (4) Problems with Technology, (5) Concept of Print. Two themes regarding strategies for by-passing the ADA/accommodation request process: (1) Habit, (2) Successful Means of Acquiring Accommodation. Negative responses to accommodation requests inhibit future accommodation requests; barriers indicate to people that avoidance of ADA request process is preferable. |

Continued evaluation of the ADA request for accommodation process. More research on people in disabling environments requesting and receiving/not receiving accommodations. |

Input from people with disabilities about experiences with ADA request process is necessary to develop solutions to these problems. |

Not a diverse sample in terms of age or race (all Euro-American ethnicity, ages 37 to 65). Results not generalizable, research cannot estimate prevalence of barriers or successes from the ADA. Participants may have elite bias. |

|

Hazer, J. T., & Bedell, K. V. (2000). Effects of seeking accommodation and disability on pre-employment evaluations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(6), 1201-1223. |

Stone and Colella’s (1996) interactive model of factors affecting treatment of PWD in organizations. |

Study explores whether accommodations and disability type influence perceived suitability of hiring a job applicant. Hypothesis 1 - Job applicants who seek reasonable accommodation will be rated less suitable for hire than will job applicants who do not seek accommodation. Hypothesis 2 - Job applicants with a psychiatric disability will be rated less suitable for hire than will applicants with a physical disability. Hypothesis 3 - Job applicants with a disability will be rated less suitable for hire than will applicants with no disability. |

Participants (n=144) were human resource professionals (n=32) and undergraduate psychology students (n=112). |

Quantitative-Primary Data or evaluation |

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the five conditions and presented with scenario that they needed to hire a bookstore clerk. Participants reviewed job description, resume, and interview transcript and then completed the measures/scales. Seeking Reasonable Accommodation and Disability Type; DVs (scales) were ADA Knowledge & Attitudes and Employment Suitability. HR Employment Status was included as a covariate. Results were analyzed using ANCOVAs. |

No funding source provided. |

Asking for reasonable accommodation lowered employment suitability ratings (even after controlling for HR employment status). Suitability ratings significantly higher for nondisabled applicants compared to psychiatric disability applicants but not significantly higher compared to physical disability applicants. HR professionals gave lower suitability ratings than did student participants. ADA Knowledge/Attitudes did not influence perceptions of suitability of specific job applicants. Findings imply that disclosing a disability & requesting accommodation may be better received only after the extension of a job offer. |

Research needed on employees who acquired disability after being hired. Research needed to explore if job type (private/public, service/manufacturing) affects employer receptivity. |

Vocational rehabilitation counselors should educate clients about disclosure, negotiations, and strategies for gaining/maintaining employment. |

Use of paper stimuli instead of actual employment situation with real people. Low sample size of HR employees. Type of job used in the hiring scenario may have affected results. More research needed about stereotypes held by employers and effective interventions for change. |

|

Parry, L. E., Rutherford, L., & Merrier, P. A. (1996). Too little, too late: Are business schools falling behind the times?. Journal of Education for Business, 71(5), 293-299. |

None given. |

Study surveyed higher education instructors and analyzed recent business communication textbooks to determine the extent of coverage on ADA and disability disclosure. Research Questions: Are educators in higher education addressing the ADA and is there practical discussion of when/how disabilities should be disclosed? |

Business Communication Instructors were surveyed (n=199; 33% RR); 13 textbooks were analyzed for ADA content. |

Mixed methods - Surveys (Quantitative) & Content Analysis (Descriptive) |

Method 1: Survey was mailed to stratified (geographic) random sample of business communication instructors that were members of the Association for Business Communication. Surveys asked about included course content, specifically ADA disclosure. Survey results analyzed using frequency distributions, paired samples t tests, and chi-square tests. Method 2: Analysis of current business communication textbook content was conducted to examine if disability disclosure was discussed in employment communication. All texts were copyright 1992-1994. |

No funding source provided. |

79% of instructors cover employment communication in courses taught, but only 45% covered disability disclosure in courses. Lack of coverage was found across all institutional types. Female instructors were more likely to discuss disclosure. 65% of instructor respondents had no ADA training. Zero of the 13 textbooks analyzed discussed disability disclosure, though some covered illegal questions during the hiring process. Instructors not teaching about the managerial ramifications of the ADA. Students are receiving little to no information on this topic during their formal education. |

Higher-Ed institutions and business schools should have ongoing assessment of the goals of their organization and if their goals are being met through their required curriculum knowledge base. |

Increasing external collaborations and learning, interaction with other academics in different departments, and utilizing more recent instructional materials (academic articles and recent newspaper publications) can increase awareness of the ADA. Institutions need to adopt comprehensive strategy for determining topics to be covered in curriculum. Schools should develop a common knowledge base about topics relevant to their students. |

Researchers did not attempt to secure/analyze copies of all texts available in the field. |

|

Price, L., Gerber, P. J., & Mulligan, R. (2003). The Americans with disabilities act and adults with learning disabilities as employees the realities of the workplace. Remedial and Special Education, 24(6), 350-358. |

Collective Case Study design using interviews developed under theoretical framework based in currently available professional literature from Gerber & Brown’s (1996) text. |

Study asks: (1) how do American adults with learning disabilities view their disabilities? and (2) what impact has the ADA had on employment of adults with learning disabilities? |

Adults with learning disabilities ages 19 to 32 (n=25). |

Qualitative- Interview |

Collective Case Study design utilized by collecting in-depth, in-person interviews with adults with learning disabilities. Interviews included questions about job acquisition, experiences on the job, job advancement, self-disclosure, and employer experiences/attitudes/beliefs. |

No funding source provided. |

Findings showed Title 1 of the ADA is underutilized by employees with learning disabilities. Over two thirds of participants had never heard of the ADA and the majority of interviewees did not understand or use the ADA to get their first job or self-advocate. No respondents used the ADA to accommodate them during the interview process, pre-employment testing, completing job applications, or as a candidate for employment promotion. Self-disclosure about disability was uncommon and most participants did not report requesting reasonable accommodations. No participants had asked or received any accommodations under the ADA and no participants had ever communicated to their employer(s) about the ADA. Over half of participants did not regard themselves as being learning disabled, despite documented diagnosis and receiving learning support during elementary/middle/secondary school. Adults with learning disabilities got their first jobs in similar fashion as their nondisabled peers. |

Research field currently lacks conceptual model for employment which accounts for the heterogeneity of the population of adults with learning disabilities. Assumptions about learning disabilities and their effect on employment experiences should be challenged in future research. |